In her latest Flying Solo post, Sue Littleford discusses how to edit references more efficiently (and more profitably).

When I’m copyediting, the references can take longer than the main text. There’s a lot involved and the scope of work can be quite broad – I’m often required to complete or correct inadequate references, as well as attend to all the styling issues. And on pre-edited files, there are a lot of styling issues!

So it’s clear that editing references can depress your words-per-hour rates, and a bad biblio can absorb almost the whole time or money budget just by itself. And that then depresses you!

So what can you do to avoid being out of pocket?

I recommend a two-pronged approach:

- being as efficient in your workflow and practices as you can, to keep your hourly rate nearer to where you want it to be, and

- pricing correctly for references in the first place.

If you’re not confident with references, you should take a look at the CIEP’s References course, of course!

So here are my ten top tips to make editing references more profitable.

Curtail the time you spend on them with good workflow habits

1. Be sure you know the referencing style that’s to be used

Refresh your memory even if it’s one you’re familiar with – we have to skip between different styles so often, it’s easy to start using the wrong one. I edit both books and journals for one university press, and the style for references is different for each. So I always look it up and make sure my head’s in the right place before I start.

2. Edit the references first

It eases you into the job, and then you know when you’re checking the citations that the dates, page ranges, author order and spellings you have in the refs list itself are the right ones. If you do references last, then you can find yourself backtracking over the text to correct those things, and that’s wasteful of your time.

3. Consider editing the citations next, in one go

I find this one depends on the editor and the nature of the job. I know some editors who swear this is the way to go, and others (I’m in this second camp) that check them off as they work through the text, so they are edited in context. And we all know how important context is!

Suppose you have two references: Smith and Patel 2018a and 2018b. You can see from the article titles that 2018a is about topic X and the second is clearly about topic Y. If you edit the citations out of context, you may find that the details are fine and match up. Big tick. But editing in context means that you may want to query whether 2018b was meant where 2018a was given.

However, in a law book, the footnotes may just be references to legislation and court cases, and it may be more efficient to edit those together for style and to check them off against any tables of cases and legislation the book contains. Like I said, context matters.

4. Print out the references list once you’ve edited it

I know, I know, we’re discouraged from printing when we don’t need to (I hope you’re using paper from sustainable sources, anyway, and printing double sided if you have a duplex printer). I know you can have a split screen with the references scrolling at the bottom and the text at the top.

I’ve tried all that, and I can say that – for me – having the printed references is the quickest way – especially when I’m working with pre-edited files and I don’t have the luxury of covering the references with highlighter as I mark them off. You could, I guess, have a copy of the references in a separate file, and then highlight to your heart’s content, but now it’s getting a bit messy and open to error. Errors are bad – and take up time to make and to resolve.

For author–date referencing, I tick off each reference as it’s used. For a back-of-the-book bibliography, I also note the chapter number that it’s been used in. That can be handy information later, if you’re trying to resolve problems.

For short-title referencing, I tick off each reference as it’s used. But now I definitely mark which chapter it’s been cited in, because most of the short-title jobs I have require the bibliographical detail to be given in full at first use in each chapter. I also underline the words I’m using for the short title. That way I can be sure that short or full titles are given in the correct place, and that the form of short titles is consistent throughout.

I can also jot notes to myself if I spot a missing closing quotation mark, or a reference out of its alphabetic position, or what have you, as I mark off the references as they’re used, then I make those corrections all in one go instead of dodging back and forth between text and reference.

5. Limit your fact-checking

Ensure you’re conscious of the requirements of the brief. For theses and dissertations, it may be completely hands-off for references, so don’t even start trying to fix the content, even if you’re allowed to edit for style.

Some publisher briefs will say to check all the content and find missing details, correct errors and so on, and to check links are working and go to the right thing.

Others will just want you to look at the styling. Obey the brief – don’t feel obliged to go beyond it. You’re not being paid for that work!

If you have a brief that says to correct the content of each reference, then still beware rabbit holes! We tell ourselves it’s faster to look up something ourselves than to raise an author query (AQ). That’s true, very often. But if you find yourself going to three or more sources to try to verify the details, or you’re spending more than, say, five minutes on a particularly recalcitrant reference, then know when to stop. Raise the AQ and move on to the next reference.

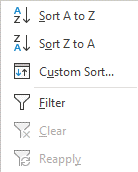

6. Be aware what macros might do for you

In his macros book, Paul Beverley has macros that will look up phrases on Google for you, or check places on a map or open Google Translate (GoogleFetch, MapFetch and GoogleTranslate). Try them out and see if they suit the way you work.

Get paid for the work: Pricing and time estimation

7. Know how long it takes you to edit a reference

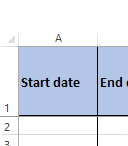

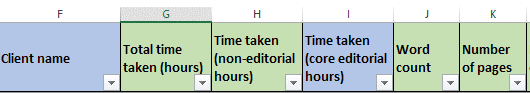

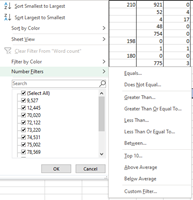

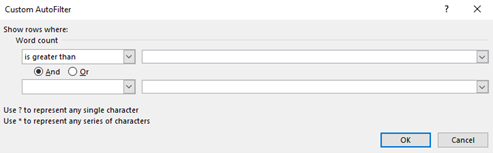

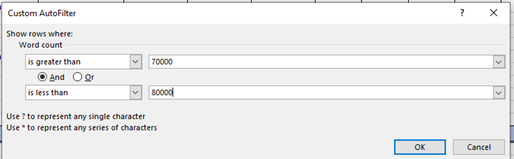

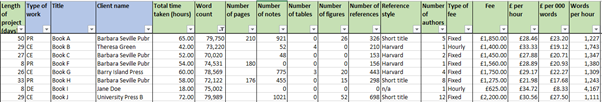

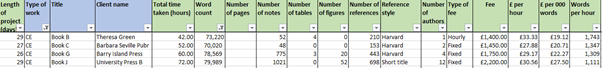

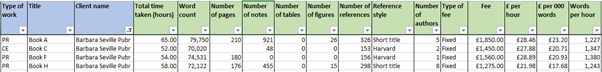

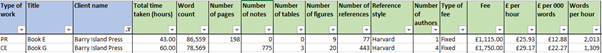

I’m serious – don’t be put off by knowing the range is anything from 15 seconds to 15 minutes or even longer. Log your time separately for references and for running text (and for tables, while you’re at it). Note the time, and how many references you dealt with (and at what depth of intervention: style only, looking things up, supplying additional details, finding replacements for broken links). Do this for a few jobs, then analyse your figures and see what your longer-term averages are. Then repeat the exercise in a year and see if you’ve got faster!

8. Know how many references are in the job before giving a price

Now you know how many references you can do in an hour, hour in, hour out, when you’re pricing a job, you can ask for the number of references, as well as what the client wants you to do with them, on top of the word count for the rest of the text and so on.

You can calculate a per-reference price separately on top of the editing of the running text, or a time-based price, depending on your circumstances and preferences.

Bonus tips!

9. Know how to handle oddities, and make notes so you don’t keep reinventing the wheel

Epigraphs? Tweets? Do you know how to handle those? The first time you encounter them, make a note (I use the notes function in MS Outlook – nothing fancy, but always findable).

Some people will tell you an epigraph doesn’t need a reference. Well, that’s not so true. Epigraphs are excluded from fair use, for instance, so it’s probably a very good idea to reference them properly.

By all means, don’t clutter the epigraph source line – name, or name and source book is probably going to be fine, but do have the information findable in the references list. Some epigraphs benefit from having the original year of publication appended, if the author is using them to demonstrate how long some ideas have been knocking around.

Well-known quotations can probably do without a reference in some publications, but not in others. If you’re working on a text that is going to omit references for them, it’s still worth checking that the quotation was actually produced by the person it’s attributed to – a lot of them have the wrong name attached.

Protect your author, even if you don’t produce full bibliographical details. Why? I once found that a plausible quotation attributed to Gladstone in fact came from the scriptwriters for the movie Khartoum. That was a rabbit hole worth diving into! Oh, and as Churchill famously didn’t write, ‘That is the type of arrant pedantry up with which I shall not put.’

Famous quotations can be infamous misquotations.

Tweets and other social media ephemera can be a challenge, so know where you’re likely to find good advice. APA, CMOS, MLA, New Hart’s Rules and others all have sections on the unusual kinds of things you may need to style (or find) a reference for.

If the style guide you’re working to omits them, there’s quite often a statement in the style guide that says which of the major published style manuals underpins the client’s own, or you can use the one that’s the closest match to the rest of the styling.

10. Stay up to date

As colleague Ayshea Wild observed to me recently, ‘It’s one of those areas where CPD is so important – citation formats are shifting all the time.’ That’s self-evident, given that we’re on APA7, CMOS17, MLA9 and so on, but it’s frequently overlooked – and house style guides also morph over time, so do be sure you have the latest version when you start each job.

So there we are: ten top tips to help prevent reference lists running away with you, and to help you be paid properly for working on them. If you have a tip you’d like to add, pop it in the comments!

Want to learn more about how to deal with references?

Check out the CIEP’s References course here.

About Sue Littleford

Sue Littleford is the author of the CIEP guide Going Solo, now in its second edition. She went solo with her own freelance copyediting business, Apt Words, in March 2007 and specialises in scholarly humanities and social sciences.

Sue Littleford is the author of the CIEP guide Going Solo, now in its second edition. She went solo with her own freelance copyediting business, Apt Words, in March 2007 and specialises in scholarly humanities and social sciences.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: books by Hermann, highlighters by jakob5200, alarm clock by Alexas_Fotos, all on Pixabay.

Posted by Harriet Power, CIEP information commissioning editor.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.