Riffat Yusuf explores our editorial role in styling informal youth language.

I was 18 years old the first time I heard wicked used as a compliment. (Why, thank you, homie.) I did a double take, but it had more to do with the pronunciation than the application – brown kids in West London trying to sound, well, browner. The second-generation aspiration of better Englishness than our parents was thrown into question by that mid-eighties neologism, and it rattled. We might not have looked the part, but the English we wrote or spoke didn’t need to be ‘exotically’ accented, did it?

I was 18 years old the first time I heard wicked used as a compliment. (Why, thank you, homie.) I did a double take, but it had more to do with the pronunciation than the application – brown kids in West London trying to sound, well, browner. The second-generation aspiration of better Englishness than our parents was thrown into question by that mid-eighties neologism, and it rattled. We might not have looked the part, but the English we wrote or spoke didn’t need to be ‘exotically’ accented, did it?

If ever there was a boomer

I actively snob-distanced from ‘youth language’. When I wasn’t being Brideshead Revisited, I was grimacing in sympathy with older people at all the yo-ing and sick-ing hurled about in public. Now I see that the volume would have been more objectionable than the vocabulary – notable exceptions being anything ending in ‘claat’ (which won’t appear in this article’s selected glossary – you’ll have to look that up yourself).

Neither I nor probably any of the people on whose behalf I tutted were aware, or cared, that ‘proper’ English was already awash with old words for new, contracted phrases and repurposed expressions. As long as it sounded English, it was acceptable. The wotcha, bagsy and faynights of the seventies were perfectly cushty, but not the sick, innit or wappnin’ of my peers in the eighties.

(Little did I know that a different set of peers had been gnashing their gums at wholly English-sounding neologisms. Where better than the House of Lords to shake a stick at ‘hopefully’?)

Life went on without my absurd loftiness. The Queen kept her English, my friends kept theirs, and I piped down. In the nineties, I came to admire a new generation of teens who refused to anglicise their conversations: why not answer your mum in the language she taught you and so what if people on the bus stared? Young people from minority communities went on to share language with friends from outside their ascribed ethnicities and were unfazed by the mutterings of well-intended purists, or worse, older imitators. Big up Gen Z!

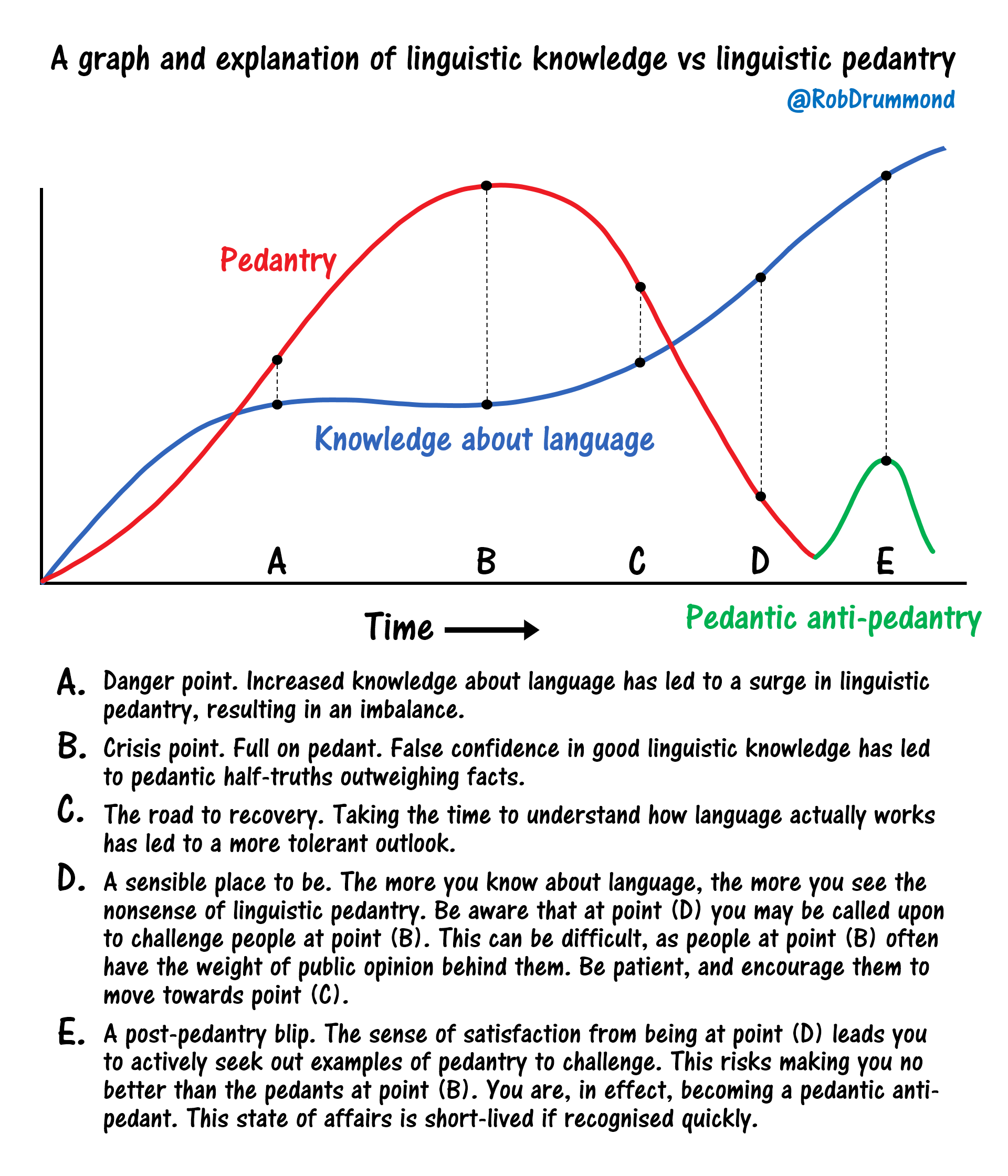

Using words to make connections, rather than to mark differences, is an approach exemplified by linguist Rob Drummond. His research finds that the modern language usage of young people isn’t defined by or limited to a specific ethnicity. I’ve seen how this translates in real life and I’m intrigued. Young children (English, Eastern European, Korean, it makes no difference) can be heard insisting that their friends say ‘wallahi’. That’s an Arabic phrase, introduced to playgrounds by Somali children, and uttered by any child holding another to account. In my day, it was ‘swear on your mum’s life’.

MUBE it

Youth language, argot, ghetto grammar, Jafakin, call it what you will for now, has been documented, translated and commented on by enough (never young) people that we editors and proofreaders should have material aplenty to do what we do best: reserve non-editorial judgement and style-guide it to consistency.

But before we strike out in red and blue, what do we even call Multicultural Urban British English? (Great, that’ll do – thank you, Rob Drummond.) Be conscious, however, of ‘the responsibilities that come with naming varieties, especially as the terms are picked up by non-professionals and used in ways that might not correspond to their original denotation’. That’s also from Drummond, the boss of non-standard. Ponder, though, for the time it takes to say no, whether anybody young enough to speak Multicultural Urban British English calls it that.

Word up

MUBE is more than a lexicon. (Strictly speaking, it’s the initialism of a bank employees’ union in Malta …) It’s not news to us that language isn’t just about words and definitions, yet we flit like outsiders to Urban Dictionary, seldom looking past the written meaning. Perhaps it’s understandable that we treat youth language as we would any other jargon we come across when editing. I have spent more time thinking about the verb/pronoun choice and stress exercised by young people than I have about the significance, for those same people, of identity markers drawn from cultures I just don’t get: cf. ‘allow it’ (put a stop to it) and ‘allow that’ (don’t do it in the first place).

Having children old enough to use youth language doesn’t qualify me to speak authoritatively about the social or cultural influences behind their bantsing. (See? And I tried really hard not to mis-gerund.) It’s a good job we have Rob Drummond to make sense for us. His ‘(Mis)interpreting urban youth language: white kids sounding black?’ looks closely at how young people use ethnolects (language and dialect associated with specific ethnicities) in ways that are overlooked, parodied or misinterpreted by most mainstream media.

Drummond’s research introduces us to contemporary insights on MUBE. By contemporary, I mean also the voices of young people themselves – it’s the first time I’ve read what young people have to say about their own language usage.

But we are time-pressed (I’m hoping you read this after the worst of coronavirus has passed and you are inundated with deadlines), so let’s start with something more breezy. Andrew Osmond’s blog is a light-hearted explanation of multicultural London English. And there’s a style-over-spellcheck treat, too – more of this to come.

Standard bearing

If I’m going to attempt a broader representation of what is said or written about MUBE, I have to slide way over to David Starkey in 2011. While I disagree with his stance on acceptable sociolects and question his take on linguistics, I will defend his right to being favourably edited even if the Guardian rendered his views verbatim: ‘This language which is wholly false, which is this Jamaican patois that has been intruded in England and that is why so many of us have this sense of literally of a foreign country.’

Marginally more instructive are online articles about urban language workshops for the police. Perhaps I’m reading too much into the ‘jolly japes’ tone of such reporting, but I feel it plays to a mindset that reifies youth language as a gang-related acquisition. It leaves Disgruntled of Middlesex indifferent to the code-shifting (adjusting language to suit an audience) that their own children are doing like a pro. You might not be able to tell grunge idioms from grime and it’s safe (hint: safe) to assume you’re not sure which adjectives also serve as affirmatives, but your children fluently navigate languages they weren’t taught at school. Oh, go on then, google ‘police beef ting’.

Once you’ve bare embarrassed yourself saying peng and wagwan out loud, and done that Westside hand gesture, please read anything by language expert David Shariatmadari to reassure yourself that the linguistic habits and word choices favoured by young people (aks instead of ask, and like with everything) are examples of processes native to standard English. Actually, his work deserves more than a passing reference; please buy Don’t Believe a Word: The Surprising Truth About Language.

Word count

Of course we understand how language works – we’re editors and proofreaders – can we just get on with attending to the words? So where, if its usage is so prolific, is all the MUBE content?

What are young people reading these days? That’s where all the editing contracts should be. My convoluted internet searches suggest publications like Nylon. But I couldn’t find any youthy words in the issues I looked at. Ditto for Accent and LADbible. I found a mandem and a few droppings elsewhere, but so far, so sparse. And then I asked a young person.

Write, right, rite

Write, right, rite

Young people are their own authors. I think they might even be curators. The provenance of their language isn’t up to them, but they own the rendering of their words in a way we mostly do not (I dare you to defy punctuation). And they don’t care or ask for our intervention. The content that they upload, even if the bulk of it seems to be captured on a phone in front of a mirror, is written up, or at the very least captioned. And boy is there some idiolect happening!

Even I’ve heard of Instagram, but rinsta and finsta? Do you know which one is interchangeable with sinsta? I’m quite impressed with the audacious exclusivity of young people’s usage. If you need a word spelled out, if you’re querying camel hump compounds, you’re not the target audience. The most recent article I could find on sta-breviation uses initial caps but is almost a year old; maybe it’s no longer a thingsta.

But how did it all go #?

Writing, says linguist Gretchen McCulloch, ‘has become a vital, conversational part of our ordinary lives’. Online writing is still edited but, as she observes in Because Internet, we are now reading words that were once only spoken.

McCulloch sees patterns in ‘beautifully mundane’ online language that can tell us more about language in general and how new words enter usage. From how we punctuate emails and texts differently (yes, I know you don’t) to keysmash (try it, I got: ajndasj.lbndf.as) to the melodic evolution of ‘mm-hm-mm’ for ‘I dunno’, this book will take you closer to understanding internet linguistics and its designated drivers: young people.

But still …

We seek order. The lens through which we look at non-standard text is held by a standard-steadied hand. For every new project, we sift through for common usage, consistency and clarity, don’t we?

Granted, when young people write for other young people, they don’t need our editorial expertise, but what about when we, #genfogey, write about young people? For each writer I’ve mentioned, I’ve triple-checked their youth language styling and I still can’t find agreed usage: is the film called Adulthood or AdULTHOOD; is galdem/gyaldem/gyal dem a nuance thing? How many ‘r’s and ‘p’s in brrupp? D’you get me, blud or blad?

Resourcelessness

Browser beware: Urban Dictionary takes you to definitions you didn’t think could exist while Oxford English Dictionary is as useful as consulting your grandmother. Wiktionary contributors may supply you with interesting but unhelpful tangents which you then have to chase up on the British Library’s website, whose advanced search options are set up for people who have the time to go to an actual library. Thankfully, we have the estimable Jonathan Green who is hundo p the authority on rude/youth words. His website, Green’s Dictionary of Slang, is a regularly updated trove of expressions with timelines and etymologies that go back centuries.

There is some guidance for editors of the future; they will benefit from OED’s appeal, which should provide an authoritative spellcheck of ‘distinctive words that shape the language’. If you are interested in how new words are added to the dictionary, this article explains.

For now and the foreseeable future, we are left with the chicken-and-eggness of New Hart’s Rules’ advice on lexical variants (youth language per se is not included in 21.7, but …): ‘it is essential to have specific guidance in the form of a dictionary and a style document to ensure consistency’. That, as the young people probably no longer say, is peak.

Glossary

bagsy a verb, often used by children, to declare a right to something before somebody else makes the same claim

bants short for ‘banter’

blad/blud from ‘blood’, a noun used to address a male – often a friend

braap/brrupp/brup an exclamation to show agreement or approval by imitating the sound of gunfire

dropping making something available (to buy, watch or listen to), usually on the internet

faynights an exclamation called out during a game to assert exclusion from the rules, or protection from disqualification

finsta a ‘fake’ Instagram account, where people often upload more private posts

galdem/gyaldem/gyal dem girls

homie/homey from ‘homeboy’ – a good friend

hundo p hundred per cent, in complete agreement

innit an elision of ‘isn’t it’, an often meaningless rhetorical marker

mandem men, or people in general

peak bad luck, unfortunate

peng attractive (used for people), nice (used for things)

rinsta a ‘real’ (public) Instagram account

safe good or cool, also signifies agreement

sick cool, awfully good

sinsta a secondary Instagram account, see also finsta

wagwan a greeting, an elision of ‘what’s going on?’

wappnin’ a greeting, an elision of ‘what’s happening?’

wicked attractive, excellent, wonderful

wotcha/wotcher a greeting, an elision of ‘what cheer’

yo a greeting, agreement (yes) and a way of addressing somebody

Riffat Yusuf is a West London-based proofreader and copyeditor, and a content editor for a small structural engineering company. She has been editing since 2018, and before that she taught ESOL for 10 years and brought up her family. In the dim and distant past she was employed in journalism, radio and television. In the future, she’d like to work on ELT resources.

Riffat Yusuf is a West London-based proofreader and copyeditor, and a content editor for a small structural engineering company. She has been editing since 2018, and before that she taught ESOL for 10 years and brought up her family. In the dim and distant past she was employed in journalism, radio and television. In the future, she’d like to work on ELT resources.

‘A Finer Point’ was a regular column in the SfEP’s magazine for members, Editing Matters. The column has moved onto the blog until its new home on the CIEP website is ready.

Members can browse the Editing Matters back catalogue through the Members’ Area.

Photo credits: silhouttes by Papaioannou Kostas; selfie by Djamal Akhmad Fahmi, both on Unsplash

Proofread and posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.

Editing would be simpler if we replaced which, that and who/m with what. No more asking why it was the boy who and not that cried wolf. No more whiching and thating Jack’s house. No more consulting BBC Bitesize Fowlers for restrictive and non-restrictive clauses. For people what need precedents, I refer you to hwæt, used extensively as a relative pronoun in the 13th century. I refer you also to more recent usage (albeit the aspirated interrogative form, inconveniently not functioning as a relative pronoun, but go with it), viz. Meg Mortimer from Crossroads: ‘Hwhat are you doing, Sandy?’

Editing would be simpler if we replaced which, that and who/m with what. No more asking why it was the boy who and not that cried wolf. No more whiching and thating Jack’s house. No more consulting BBC Bitesize Fowlers for restrictive and non-restrictive clauses. For people what need precedents, I refer you to hwæt, used extensively as a relative pronoun in the 13th century. I refer you also to more recent usage (albeit the aspirated interrogative form, inconveniently not functioning as a relative pronoun, but go with it), viz. Meg Mortimer from Crossroads: ‘Hwhat are you doing, Sandy?’ And so to trample on non-restrictive relative clauses. This much I have learned: you can recognise a non-restrictive clause in British English because it always takes which as its relative pronoun. It must be offset by a pair of commas; in a sentence, a non-restrictive clause looks like this: ‘The house, which Jack built, is in a desirable neighbourhood.’ And if you swap the commas for brackets – ‘(which Jack built)’ – it’s easier to discern the clause’s aside-like, non-essential, non-restrictive, non-defining function.

And so to trample on non-restrictive relative clauses. This much I have learned: you can recognise a non-restrictive clause in British English because it always takes which as its relative pronoun. It must be offset by a pair of commas; in a sentence, a non-restrictive clause looks like this: ‘The house, which Jack built, is in a desirable neighbourhood.’ And if you swap the commas for brackets – ‘(which Jack built)’ – it’s easier to discern the clause’s aside-like, non-essential, non-restrictive, non-defining function. Riffat Yusuf is a West London-based proofreader and copyeditor, and a content editor for a small structural engineering company. She has been editing since 2018, and before that she taught ESOL for 10 years and brought up her family. In the dim and distant past she was employed in journalism, radio and television. In the future, she’d like to work on ELT resources.

Riffat Yusuf is a West London-based proofreader and copyeditor, and a content editor for a small structural engineering company. She has been editing since 2018, and before that she taught ESOL for 10 years and brought up her family. In the dim and distant past she was employed in journalism, radio and television. In the future, she’d like to work on ELT resources.