By Ayesha Chari

‘I can’t get it done on time if you eat my head from the morning!’ Words I said aloud to my other half just before sitting down to write this. (Unusual, given that I’m the one who’s generally doing the nagging.) I am glad no one asked me to prepone submission.

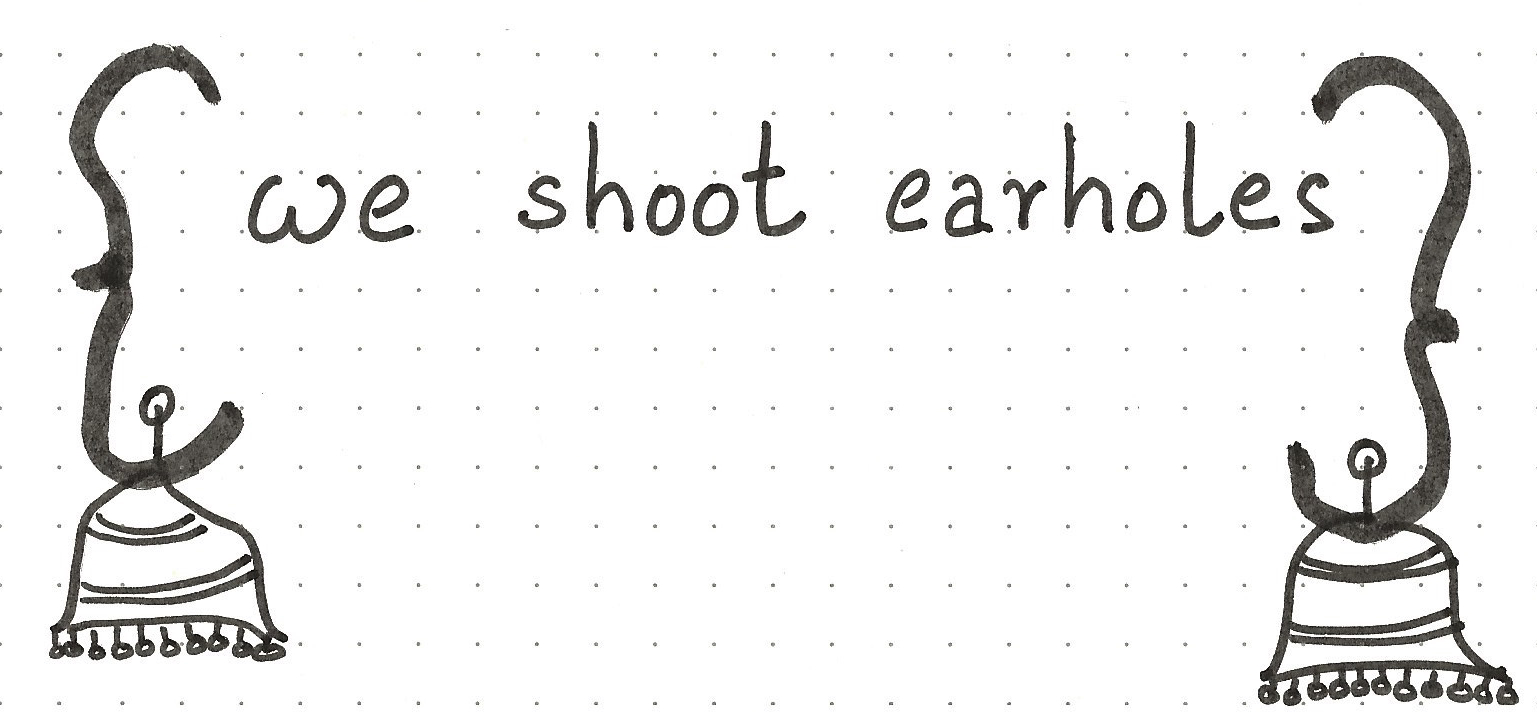

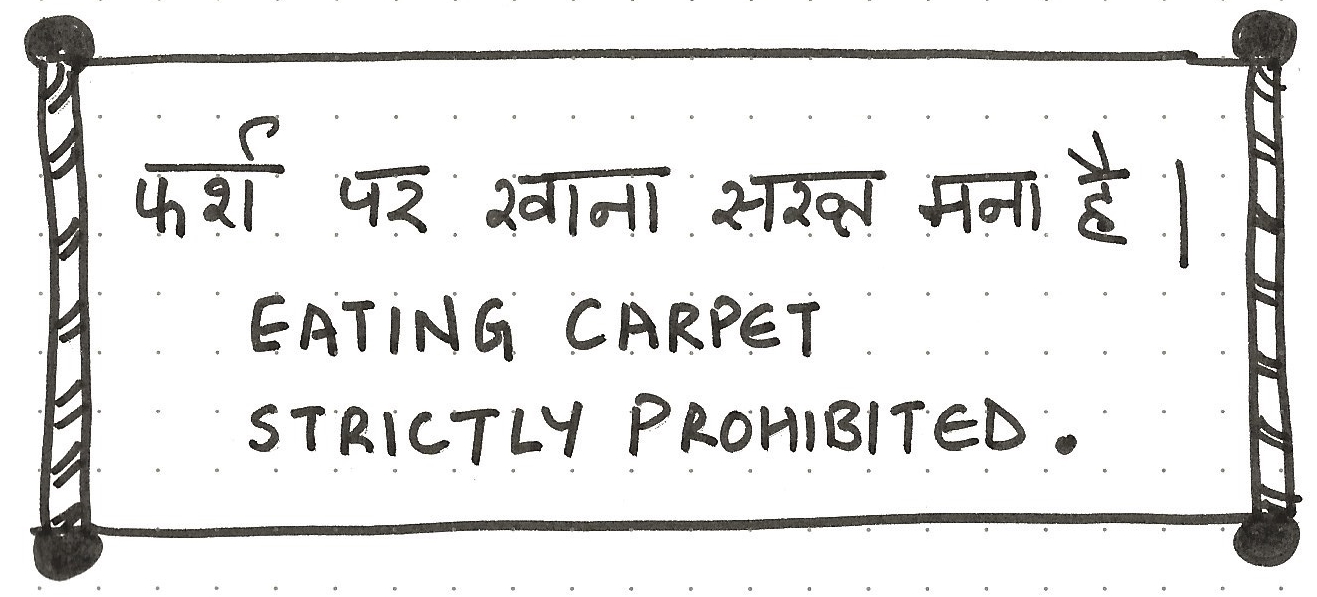

Indian Englishes are as diverse as the people who speak them, and the buildings those people inhabit.

Indian English, as is widely acknowledged, comes in as many colours and variations as people in the sub-continent. It is not the equivalent of Hinglish, not the sole domain of Bollywood, nor the caricatured ‘incorrectness’ painted eloquently in English language literature. It seeps effortlessly through urban, semi-urban and rural terrains in the spoken and the written, and is accepted as the glue binding the 22 constitutionally ‘scheduled’ Indian languages and hundreds of other language-dialects, recognised or otherwise. Not without contention, of course, perhaps highlighted most by the ‘non-native English speaker’ label forced on the nation’s people by bureaucratic forms in all fields and worldwide.

Historically, introduced to the Indian elite via the East India Company, the formal teaching of the English language was established with Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education and the English Education Act of 1835. Taking a shape of its own in post-colonial South Asia, ironically English became the tape for a linguistically and culturally fragmented nation and its Indian diaspora. Among the earliest documented works on the characteristics of Indian English is linguist Braj Kachru’s 1961/62 thesis, available from the University of Edinburgh Research Archive (Prof Kachru’s The Indianization of English and The Alchemy of English are widely used as references in the field). The controversial 2019 Draft National Education Policy re-emphasises the three-language formula first introduced in 1968, leading to questions on the role of English as a link-language for bilingual citizens of a multilingual nation.

A basic internet search on Indian English will throw up scores of researched articles and resources (old, not-so-recent and more recent) on:

A basic internet search on Indian English will throw up scores of researched articles and resources (old, not-so-recent and more recent) on:

- the history: British, but also Portuguese and Dutch influences;

- extent of use: exponentially growing, as I write;

- characteristics:

- British in formally taught style, grammar, spelling and punctuation – a legacy of colonisation

- increasingly American in business, spoken and other forms of quick communication – the unquestionable influence of TV, social media and globalisation of the sub-continent’s ‘service face’

- respectfully Indian in colloquial usage written and spoken – expansively mixed in idiomatic usage and everyday writings;

- vocabulary, phrases, expressions, idioms and pronunciation: all distinctly Indian, reflective of regional vernaculars, all as diverse as the nation itself.

It won’t come as a surprise, then, if I say there are no standard resources, manuals, guides or websites to help editors edit.

For useful discussions on the myriad issues, pop in to the Facebook groups Indian Copyeditors Forum and the Editors’ Association of Earth. To keep up with contemporary urban lingo, bookmark Samosapedia. Interesting, informative reads include Kalpana Mohan’s An English Made in India (2019), Binoo K John’s Entry from Backside Only (2013) and the multi-authored Chutnefying English (2011).

For useful discussions on the myriad issues, pop in to the Facebook groups Indian Copyeditors Forum and the Editors’ Association of Earth. To keep up with contemporary urban lingo, bookmark Samosapedia. Interesting, informative reads include Kalpana Mohan’s An English Made in India (2019), Binoo K John’s Entry from Backside Only (2013) and the multi-authored Chutnefying English (2011).

And then there is the kaleidoscope of Indian English literature: from the traditionally recognised writings of Salman Rushdie, Mulk Raj Anand, RK Narayan, Ruskin Bond, Anita Desai, Nirad C Chaudhuri and Vikram Seth to the engaging, controversial, academic, popular (yet, often, quieter, less talked-about) and/or award-winning literary works of Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, Kamala Markandaya, Arundhati Roy, Arvind Adiga, Vikram Chandra, Jeet Thayil, Amitav Ghosh, Nissim Ezekiel, Gieve Patel, Kamala Das, Anuja Chauhan and Chetan Bhagat, to those of Jhumpa Lahiri and Amit Chaudhuri, writing in English but not agreeing with the label of the genre, the list is endless and reveals there is no standard written form. And new tales continue to be embraced over chai and aadda.

Bottom line: Being aware of regional sensitivities, variations, expressions and context is key to recognising and understanding ‘Indian Englishes’ for their own sake. Because we are like this only.

Dear Ms Cathy,

Thank you to blog team for asking me to write up.

Please find herewith my draft blog contribution.

Please let me know if you wish to know any further. I will do the needful and revert back.Sincerely,

Ayesha

Disclaimer: No offence is intended to native or non-native speakers of any language. All errors and inconsistencies are the author’s and the editor’s, who are both same-to-same.

Disclaimer: No offence is intended to native or non-native speakers of any language. All errors and inconsistencies are the author’s and the editor’s, who are both same-to-same.

Ayesha Chari is an Indian editor with ancestral, native and adopted linguistic roots in New Delhi, Benares and Lucknow (northern India), Behrampore, Dhanbad, Arrah and Calcutta (eastern India), Bombay (western India), and Madras, Madanapalle and Palakkad (southern India), not to leave out Rangoon (in now Myanmar) and Jessore (in now Bangladesh). Currently based in the UK, she has done the needful, sat on the computer and written – in true character of the topic – twice the number of words Catherine Tingle requested for this blog. When not doing timepass, she teaches her 2.5-year-old Indian English among other languages.

Ayesha Chari is an Indian editor with ancestral, native and adopted linguistic roots in New Delhi, Benares and Lucknow (northern India), Behrampore, Dhanbad, Arrah and Calcutta (eastern India), Bombay (western India), and Madras, Madanapalle and Palakkad (southern India), not to leave out Rangoon (in now Myanmar) and Jessore (in now Bangladesh). Currently based in the UK, she has done the needful, sat on the computer and written – in true character of the topic – twice the number of words Catherine Tingle requested for this blog. When not doing timepass, she teaches her 2.5-year-old Indian English among other languages.

Lynne Murphy discusses a standard Global English and editing English for global audiences in a CIEP focus paper: In a globalised world, should we retain different Englishes?

The CIEP is no longer using the terms ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ to describe English language familiarity and competence. Where these terms appear on our site or within our materials, it will be to honour an author with relevant lived experience or to highlight their problematic use.

For more information, please read ‘”Non-native” and “native”: Why the CIEP is no longer using those terms’.

September 2021

All illustrations by Ayesha Chari.

Posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.

Loved it, Ayesha!

Thank you, Anita!

Truly superb! Delightful, informative and enticing. Thank you

Glad you found it informative, Stephen!

Had so much reading this, Ayesha! Loved the illustrations. Spot on!

Thanks, Sucharita!

In para 2, 3rd line, after “English language literature.” you should add ” and English-language movies, e.g. Peter Sellers’ mimic of Indian English”. Otherwise a scream and spot on.

Ma

Didn’t think of that, Ma! Quite right to include films, though unlike literature I think those of the early twentieth century particularly are often more telling of the filmmakers than the subcontinent and its people.

Its Super Cool Ayesha, enjoyed every bit of it!!!

Thank you, Ruchika!

Loved every word of it, ” rats were running in my stomach”, but I still read on, despite “the pangs of hunger”…which The words in quote mean in Indian English, translated straight from Hindi.

Indian English has its own flavour, but we need to be able to embrace it and bring it proudly into our writing.

Thanks for reading, Cora!

Dear Ayesha

You went to so much trouble to share this article with us, putting your heart on the line. I agree with all the earlier comments about how delightful it is. Your illustrations add so much information and atmosphere. Thank you for twice the number of words!

Thank you, Anne! It was fun putting it together.

The email in the end is the most interesting part of the article! As a former editor, I feel my hands itch to make certain changes to it

Nothing particularly unclear about it, though (besides, maybe, a missing article)! To change or not to change, the dilemma of all editors. 🙂

You did the needful so well!

Haha! Thank you for reading, Alex!

A very interesting post, which has been shared in Editing Community—another Facebook group that’s worth checking out. 🙂