The Art of Querying, a new CIEP course, is on its way. Its creator, Gerard M-F Hill, gives

us a speedy tour through questions and queries, and what the course offers editors

and proofreaders.

Is the current King of France bald?

Is the current King of France bald?

Questions are of many kinds, and not all of them are good questions – or even answerable.

Whatever you edit – advert, magazine, novel or research paper – you soon start asking yourself questions. What does this mean? Where did those come from? How am I supposed to know that? Is that all? Or even just: why? Of course queries should be clear and concise, but it’s good to be constructive too. What makes a good query?

Before you fire off a query, ask yourself what the problem is. You need to have a reason for asking, because the author may not think it is a problem at all. You first identify the problem by analysing what is bothering you. As a result, you will craft a better question and often you will identify an answer (or answers); then the author just needs to say yes (or no, not exactly … more like this).

Might I suggest?

As queries take up the author’s time (as well as yours), it is only common courtesy to keep them as few and as short as possible. So you need criteria to decide when to ask a question, and you also need a range of suitable formulas that you can adapt for each situation. Good questions will help to ensure that you get a usable answer.

Queries can be short, but they don’t have to be abrupt. It pays to be diplomatic. There are good ways to approach an author, to frame a question and to follow up an incomplete answer – and there are some even better ways.

Does it match the brief/blurb?

Who is this publication for? What will readers want to know? What will they expect to find? What are they expected to know already? Will they know all these facts, names, words, idioms, allusions or connections? Will they resent the presentation as either patronising or trivialising?

As an editor, you ask yourself such questions because they are a big part of the expertise that you offer and that your client is paying for. A publisher does not wish to hear of such defects from unimpressed reviewers or disenchanted readers.

Does it make sense?

What is the writer trying to say? Are they getting their message across? Does it make sense? Why is this different from that? You ask yourself such questions on behalf of the reader, who should not be left to wonder and has no way of asking the author to explain.

If it doesn’t make sense, if the plot or proposition doesn’t add up, if defective grammar is stuffed with malapropisms or other unsuitable words, the reader will soon drift off and never return. The editor aims to prevent any such crisis by smoothing the reader’s path so they can be informed, educated or entertained without being tripped up, distracted or misled.

Are you happy with this?

Where possible, make it easy for the author by presenting your query as a simple choice: A or B? This, that or the other? Would this [rewritten sentence] represent what you are saying?

Have forgotten something?

It’s easy to see that ‘you’ is missing in that sentence. It’s not so easy to spot when a whole topic or aspect of a piece, or the dénouement of a subplot, has been overlooked. The questioning editor keeps a lookout for content that the reader may be expecting, but which is not there.

Easy questions

Why is water wet? This penetrating question from a thoughtful child nonetheless demonstrates that ‘the greatest fool may ask more than the wisest man can answer’, though children are not fools. The saying is often attributed to King James I and VI.

In checking the reference (as all good authors should) I found to my surprise that the aphorism did not come from the wisest fool in Christendom, but from Charles Caleb Colton’s Lacon, published in 1820. In non-fiction, references – inadequate, unconvincing, mangled or missing – usually generate half your queries.

Here’s the answer!

Between 2010 and 2019 I regularly ran a session at the SfEP conference on The Art of Querying, and since then I have been expanding this workshop into an online course. It begins with the whole question of questions. For a start, what do you need to ask yourself? Can your author query be answered at all? Is there only one way to answer it? Could it be misinterpreted? Does the text assume the answer to an unspoken question?

The course next looks at questions to ask the project manager, with a checklist, and how and when to approach the author, with examples of how to do it and what not to do. This section discusses practicalities, from typefaces to time zones, alongside the principles and professional ethics that underlie all editorial queries. It Looks Funny examines your five options before you ask anything, followed by advice on formulating queries and notes, with six rules to help you.

Readers struggle with four major problems – inconsistency, ambiguity, omission and error – and each of these topics has a whole section of the course to itself. Different types of content have their own pitfalls, so there are sections devoted to prelims, narrative and argument, vocabulary and terminology, references, tables and artwork.

The Art of Querying is meant to be instructive, stimulating and enjoyable while extending your editing knowledge and skills, with lots of questions (and answers), well over a hundred real-life examples, copious but concise study notes and a variety of exercises to let you think through different solutions, along with a decision tool to determine whether and what to query, six rules you can follow and a dozen checklists for you to download and use. The Art of Querying is also (I hope) a good read and good fun!

Find out more about The Art of Querying

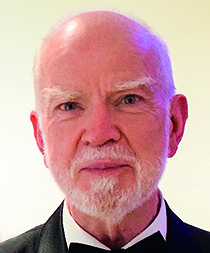

About Gerard M-F Hill

After several years teaching and 16 years driving heavy lorries, Gerard retrained as an indexer and copyeditor. Since 1990 he has worked on over 500 books and mentored over 100 proofreaders.

As a director of SfEP (2007–16) he devised the basic editorial test used by CIEP and as chartership adviser (2016–20) he worked with the chair, Sabine Citron, to obtain the institute’s Royal Charter.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: question mark by Emily Morter; Answers 1km by Hadija Saidi, both on Unsplash.

Posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.

I have three rules for myself when it comes to queries. ALWAYS be polite – the word ‘please’ goes in nearly every query. Never ask either/or questions – what do you do with the answer ‘yes’? ( If there do seem only to be two options, I formulate the query as: Is it this, or that – or something else? Please advise.) Finally, never just say something’s amiss without suggesting a way forward – unless you really are totally flummoxed, in which case, say that (nicely).