Publishing can be a mysterious process to a first-time author. Philippa Tomlinson looks at what is expected of an author at the copyediting and proofreading stages of the editorial workflow: specifically, receiving and responding to queries.

-

- What are author queries, and when are they raised?

- What might a copyeditor/proofreader ask?

- How should an author respond to queries?

*This post assumes there is a publisher, and that the copyeditor and proofreader are independent professionals commissioned by the publisher but familiar with the publisher’s house style etc. However, much the same will apply to an independent author employing a professional copyeditor

*This post assumes there is a publisher, and that the copyeditor and proofreader are independent professionals commissioned by the publisher but familiar with the publisher’s house style etc. However, much the same will apply to an independent author employing a professional copyeditor

or proofreader.

What are author queries, and when are they raised?

Having submitted the final draft of their manuscript, a first-time author might think their work is done. But hold on, who are these new emails from and why all these questions? And what does AQ mean anyway?

Author queries (AQs) form an essential part of the editorial process and, as the name implies, require the active participation of the author. Yet it is a stage that often takes a first-time author by surprise.

The bulk of AQs will be raised at copyediting stage, but there will be another round at

proof stage.

The CIEP’s fact sheet on the publishing workflow explains where the copyediting and proofreading stages fit in.

Download The publishing workflow fact sheet

Queries at the copyediting stage

The copyeditor will be the first person to go through the manuscript in really close detail. They will be interrogating the text with a critical eye: not in the negative sense of finding fault or pointing out mistakes, but with the aim of making the text the best possible version of itself.

And this involves asking questions of the author – AQs or author queries – on anything the copyeditor can’t resolve themselves or on any changes they have made which need the author’s approval or confirmation.

A copyeditor will usually contact the author not long after they receive the manuscript, introducing themselves and explaining briefly what their role is. They may send a set of initial general queries. They will also give the author an idea of when to expect further detailed queries and when to send responses.

Queries at the proofreading stage

Once a text reaches proof stage, it’s looking pretty much like the final product. A first-time author might be tempted either to just admire the clean pages or, seeing their text in this new presentation, to embark on a series of changes.

But no, their role is to read and check, and to respond to another set of AQs, this time from the proofreader, who will be reading the proofs with a fresh and critical eye.

Again, the proofreader will make an initial contact with the author, introducing themselves, alerting the author to expect queries and giving a deadline for the author’s responses.

*Note that although we have assumed direct communication between the author and the copyeditor/proofreader, it may be that a project manager or desk editor is the point of contact between the parties during the editing and proofreading stages.

What might a copyeditor/proofreader ask?

What might a copyeditor/proofreader ask?

Copyeditor

A copyeditor’s initial general queries may be establishing whether to refer to the main sections as chapters or units; asking the author to supply, say, missing concluding paragraphs to chapters X and Y; checking the author is happy for ‘data’ to be changed from singular (in the original manuscript) to plural (house style).

No two copyeditors will come up with the same list of queries on a given text. Typically, though, as they work through the text in more detail they will query if they:

- think something needs more explanation

- suspect something may be missing

- consider the text may be assuming too much knowledge on the part of the reader

- believe something could be better presented in a different way, such as a table or

a diagram - genuinely don’t understand what the author is trying to say

- spot inconsistencies or ambiguities

- identify any inherent contradiction

- want advice on preferred context if there is repetition.

All the time, the copyeditor will be putting themselves in the place of the reader,

anticipating anything that might diminish the usefulness, accuracy or enjoyment factor

of the published text.

The copyeditor will also decide what not to query and will use their skills and expertise to make small-scale, non-contentious changes or corrections to spelling, grammar, punctuation, facts such as dates and so on themselves – guided by the five ‘c’s of copyediting to make the text as clear, consistent, correct, concise and comprehensive as possible.

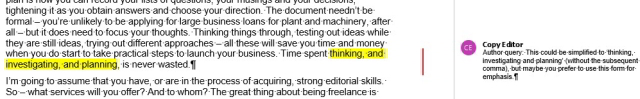

Here are some examples of a copyeditor’s AQs:

- ‘Mouth movements’ and ‘Handwriting’ are now subheadings under ‘Movement’. Are you happy with this?

- Robertson 2019 isn’t included in the references, but there is a Robertson 2018 listed. Please check dates/details and let me know any changes required.

- The table isn’t mentioned in the text – where would it be appropriate to add ‘(see Table 1.1)’ (or similar)?

- NICE guideline CG23 has been superseded by CG90 – please review and update this paragraph.

- You use ‘mute’ here – do you mean ‘moot’?

- ‘There are six variables taken into consideration’: only five variables are listed/explained. Please check/revise to include the sixth.

Proofreader

The proofreader will be picking up on anything that was missed at the copyediting stage (assuming there was one) or perhaps on some unforeseen knock-on effects of solutions to earlier AQs.

They may also be querying a puzzling cross-reference, a mismatch between the wording of a chapter heading on the contents page and at the top of the chapter opener page, or perhaps suggesting a solution to an awkward page break or an overlong page.

Here are some examples of AQs on a set of first proofs:

- ‘More recent proposals to make divorce easier would also not be concerning to the New Right’ – is this as you intended? Why the ‘not’?

- Please add in the AO marks breakdown as necessary (cf. Book 2).

- Date of the presidential election was given as 1 November 2020. I’ve changed this to 3 November – please check/confirm.

How should an author respond to queries?

There is no set way or format for recording and responding to AQs. The copyeditor/proofreader will describe their (or the publisher’s) preferred system and set out clear instructions about how the author should log their responses. Authors are advised to follow those instructions closely!

The most usual systems are listed below, but as technology evolves so will new and possibly more refined and efficient systems emerge.

- AQs logged in Word’s Comments in the edited version of the manuscript.

- AQs embedded in the edited version of the manuscript, formatted in a distinctive style/colour.

- AQs logged in the Comments bar of a PDF, tagged ‘AQ:’ or ‘Author query:’.

- Any of the above and a separate Word document with the AQs listed as a table.

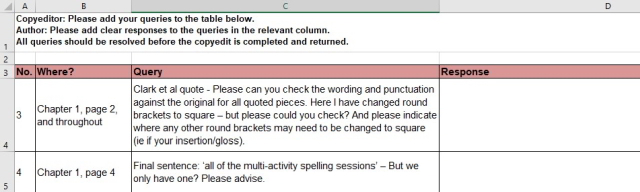

- AQs logged in a spreadsheet.

In each of the above, the author will add their responses as instructed. The author shouldn’t make any ‘silent’ changes to the edited manuscript itself.

Here is an extract from a table of copyeditor’s AQs, including the author’s response:

| Reference | Query/Suggestion | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-lexical sound–spelling correspondences | ‘Jolliffe, … agree’: Is this just Jolliffe? (Or ‘Jolliffe et al … agree’?) | Could we change the whole line to: ‘Joliffe et al, in their guidance for teaching synthetic phonics in primary schools, agree:’ |

Here is an extract from a table of proofreader’s AQs, again with the author’s

responses included:

| Reference | Query/Suggestion | Response |

|---|---|---|

| p35 – KT | Add ‘of identity’ after ‘aspects’? | Agreed |

| p35 – summary | Transpose points 6 and 7 to reflect order of content in the main text? | Agreed |

| p41 – top | Can this be updated now? | Done, on my notes |

| p43 – ‘Dual-heritage …’ / p24 | These refs to ‘intermarriage’ and ‘intermarry’ are fine, and tally with the answer to KC3. However, on p24 ‘intermarriage’ is used (I think) in the other (and opposing) sense of the word. This could be confusing. I suggest changing p24 to read ‘marriage within their class/social group’ or similar. Please advise. | I agree, change the ref on p24, if anything it should be ‘intramarriage’, but I think your suggestion is clearer. |

Authors need to be as clear as possible in their responses. They should also check, double-check and look for any knock-on effects before returning them. Follow-up queries on unclear or problematic responses can add time to what may be a very tight schedule. At proof stage, authors must also be aware of space implications. And, of course, keep to the deadline!

A final word

It can be daunting for an author to receive a list of questions on what they thought was a final version of their text, and especially so if the publisher did not inform them in advance about this stage of the editorial process.

Furthermore, the process of going through the queries one by one can be tedious in the extreme. It can also be time-consuming, so authors are advised to check their own schedules to allow for this.

That said, AQs can be the main form of communication between author and editor, the basis of a fruitful working relationship, and a useful record of decisions made for further down the line. And the end result will most certainly be a more polished version of that final manuscript.

Querying: CIEP resources for editors

- Fact sheet: Good practice for author queries

- Online course: The Art of Querying (coming soon)

About Philippa Tomlinson

Philippa worked in-house as a desk editor and a commissioning editor before going freelance. She has edited and proofread fiction, non-fiction, reference, travel writing and educational materials, now specialising almost exclusively in the latter. She has also worked as a bookseller, a library assistant and a teacher of English as a foreign language. Philippa is a Professional Member of the CIEP.

Philippa worked in-house as a desk editor and a commissioning editor before going freelance. She has edited and proofread fiction, non-fiction, reference, travel writing and educational materials, now specialising almost exclusively in the latter. She has also worked as a bookseller, a library assistant and a teacher of English as a foreign language. Philippa is a Professional Member of the CIEP.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: letter beads by Linh Pham on Unsplash; question marks by Gerd Altmann

on Pixabay.

Posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.