By Liz Jones

‘A picture is worth a thousand words.’ We’ve probably all heard this said, and perhaps we’ve even said it ourselves. But – as so often in life – the truth is not as clear-cut as that. In the materials we edit, it’s not always a case of either-or, words versus pictures. Often text and images work together to convey complex information. But the figures that support a text (or that a text supports) can only function at their best if they are commissioned carefully to work as part of a complete editorial package, and if any text associated with them is written, edited and proofread just as carefully as the main or body text.

What is a figure?

What is a figure?

In CIEP courses in the core skills of proofreading and copyediting, a figure is defined as ‘any piece of artwork (line-drawing, photo, graph, etc), together with its caption’. Figures appear in all genres of book, from children’s picture books and stories to textbooks, workbooks, technical manuals, and all kinds of non-fiction books – from practical to aspirational to academic. Aside from books, we encounter them in all sorts of written communications, from newsletters and press releases to websites, reports, white papers, advertisements … In short, where don’t we find them?

But editors are word people, you might be thinking. Aren’t images beyond their remit? Well, no. Considering the images that work alongside the text – and are often indivisible from its key message – is a crucial part of most copyediting or proofreading work.

Aside from the image itself, a figure will usually have a title or caption, which the CIEP defines as ‘the explanatory words that appear below (or above or beside) an illustration or figure’. There may also be annotations (very short labels) explaining specific parts of the figure, either placed in the relevant position or connected with leader lines.

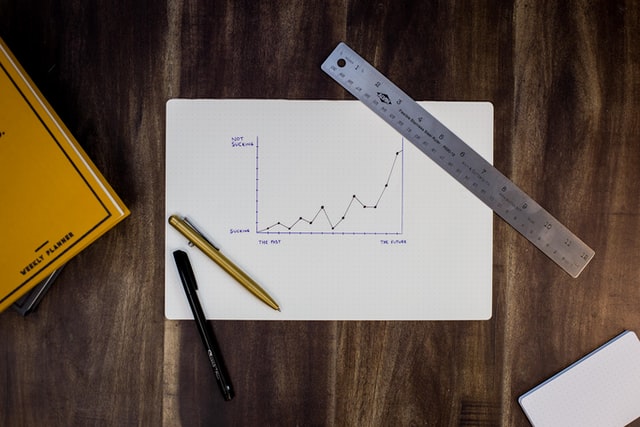

If the figure is a graph or chart, the axes or sectors will also be labelled with text.

Purpose and function of figures

Figures might be used in text for various reasons:

- They give the reader information that cannot be easily or effectively expressed using text alone.

- They can be used to amplify or clarify the message of a passage of text.

- They work as visual devices that break up large amounts of text and make it more readable.

- If the document is about a visual subject, the figures might be more important than the text, even if both are necessary.

How to write a good brief

Sometimes editors are responsible for writing the briefs for figures, whether they are illustrations, photos or graphs. This is especially likely if the editor is project managing or development editing.

The person producing the image, or the picture researcher, will need as much information as you can provide on the following:

- What information the image needs to convey – this might include a sketch, or it might be a list of points to cover

- Size of the intended image

- What colours to use

- Guidance on the preferred style

- Any cultural considerations, such as images that are not suitable for a particular audience

- Visual reference materials, if available and helpful

- The budget – most images are not free!

Reproducing or redrawing figures

Reproducing or redrawing figures

If figures are reproduced from another source, or even if they are redrawn based on another source, then the copyright holder of the original image will need to give you permission to use that figure. They might charge a fee for this, or they might simply stipulate how they should be credited. Some credit lines must appear alongside the figure; others can be placed at the end of the document.

Make sure you allow time in the schedule for clearing image permissions.

Writing and editing figure text

Captions should ideally be written in such a way that that they could stand alone and provide useful information about the figure, even if the reader reads none of the other text. Of course, we probably tend to hope that the reader reads every word we write from beginning to end. But in the real world, we have to accept that this doesn’t always happen. People have short attention spans, and they skip about when they read. Captions should also not simply repeat body text word for word, but add to it, and give the reader specific information on the visuals. For a document to feel authoritative and valuable, it’s crucial to write captions that work hard.

Everyone’s life is made much easier if text that appears as part of the figure is editable, though this is not always possible. If it’s not editable by someone with easy access to the files, make sure to get it proofread early, to allow changes to be made by the illustrator, for example. Bear in mind that the more words appear as intrinsic elements in images, the more of a problem this will be for any editions of the publication in other languages.

When an editor is assessing the scope of their work, they should make sure they include the figures in their fee calculations – both checking their content from an editorial point of view and editing any associated text, which can add considerably to the overall word count and the time needed for the job.

Checklist of common problems

Finally, for anyone tasked with proofreading figures, here are some common problems that crop up time and time again:

- Figure numbering – out of sequence, missing numbers, inconsistency

- Annotations pointing to the wrong part of an image

- Inconsistent capitalisation of captions or annotations

- Inconsistent punctuation of captions or annotations – especially terminal full stops

- Captions repeated, or applied to the wrong image(s)

- Captions that seem to contradict the image (for example referring to a colour that looks different in the picture)

- Figure is flipped, so text is back to front.

The most important message in all of this is that figures appearing as part of a document should be considered at every stage of the editorial process. They should not be dismissed as being mere design elements, or someone else’s responsibility. When authors and editors ensure that figures and text work together effectively, they are a powerful tool for communication.

Liz Jones has been an editor since 1998, and has worked on thousands of projects, involving millions of words and a whole host of other variables. She specialises in highly illustrated non-fiction for a range of clients, and also works as a commissioning editor on the CIEP information team.

Liz Jones has been an editor since 1998, and has worked on thousands of projects, involving millions of words and a whole host of other variables. She specialises in highly illustrated non-fiction for a range of clients, and also works as a commissioning editor on the CIEP information team.

Photo credits: flowers by Edward Howell; chart by Isaac Smith, both on Unsplash.

Posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.