Picture books may have some of the shortest word counts of any books, but that doesn’t make editing them straightforward. Lisa Davis explains what editors and authors need to consider when using the format of the book itself to build the story.

When initially editing a manuscript without illustrations, it’s important to consider what the illustrations can bring to the narrative. Some manuscripts might come with illustration suggestions embedded in the text to help get an idea of what the author envisions. The author may also have broken down the manuscript into page splits, but if the editor or the author is not familiar with the picture book format or editing picture books, it can be easy to overlook the importance of page turns.

Using the picture book format

The standard picture book on the market these days is 32 pages. This includes all front and end matter, which often takes up a minimum of three pages for title page and copyright information. The text itself is usually around 500 words – it’s a lot of story to pack into a small amount of space, and that’s why the format of a picture book matters so much.

Whatever the production stage, but particularly when developmental editing a picture book, an editor needs to think about the book in spreads – the two pages that face each other compose one spread. This is essential when commissioning artwork since the illustrator will need to know if they are illustrating a single page or an entire spread. Picture books can have a mixture of artwork sizes throughout, so they could take up an entire spread, a single page or even just part of a page that features several illustrations. These all aid with the pacing of the story. But, along with the pictures, we can also use the format of the book to help pace and build tension in the story.

With each turn of a page, you can completely change the scene or tone. It’s almost like a lift-the-flap book where you reveal something to the reader. Imagine the story being read aloud to a child and pausing before turning the page to ask, ‘What do you think is going to happen now?’ Or the way a scene may be cut in a film or TV programme where something is shown that contradicts what was just said for humorous effect. Or even panels in a graphic novel where you build up to something big that needs a whole page of its own.

How to use page turns

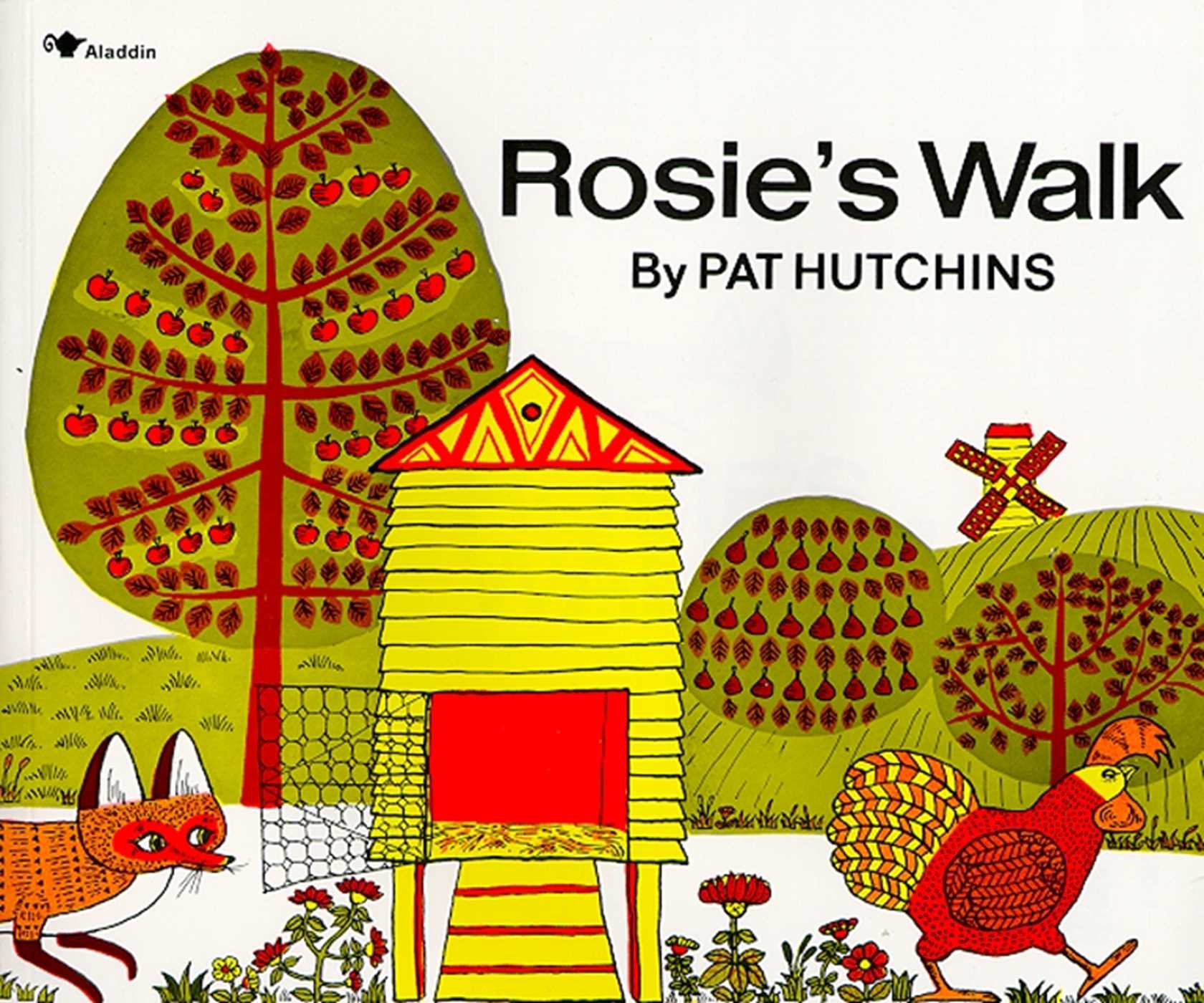

While most picture books today will use page turns to some extent, certain titles rely on this element for comedy, surprise or dramatic effect. One great example is the classic Rosie’s Walk by Pat Hutchins, which uses the page turns throughout the whole story for comedic effect. While Rosie the hen goes on a walk around the farmyard, a fox follows behind her planning to attack, only for the page to turn and the fox has a mishap that results in Rosie (unknowingly) escaping.

Unless the story fully relies on page turns, as in Rosie’s Walk, it’s more common to use these page turns for scene changes sparingly for greatest effect, usually around the climax of the story. For instance, the book I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen uses a page turn as Bear makes a realisation that yes, he has seen the hat he’s been looking for. The previous page leads to this with a ‘Wait a minute …’ moment, letting the reader know something big is going to happen once they turn the page. And then – page-flip – we zoom in on Bear’s face as his mood changes from sadness to rage, illustration turned from subtle tones to awash with red. The rest of the story hinges on this moment, which is why it’s vital to use every element a book offers (text, artwork and format) to build up to it.

Another popular page-turn technique in picture books is using the very last page of the book (which will be a single page that faces the inside of the cover) to add an illustration vignette to suggest what might happen after the story has ended. For instance, maybe you think a character has learned a lesson, but then the illustration suggests the same situation is about to happen all over again.

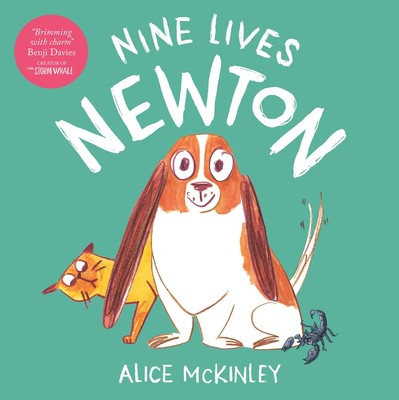

A great example of this final-page usage is Nine Lives Newton by Alice McKinley. At the beginning of the book, Newton the dog mistakenly reads an obscured sign and now believes that dogs have nine lives, setting him off to do all the things he had previously avoided doing – with a poor cat following behind trying to warn him (while using up its own nine lives in the process). By the end of the book, Newton learns about his error, and our cat friend thinks all is well again. But on that final page, a vignette shows Newton looking at another obscured sign leading to yet another misunderstanding, suggesting to the reader that the chaos is about to start all over again! It’s a great way to end the story with an unexpected laugh.

Adding page turns to a manuscript

It might be easy to see the strength of a clever page turn when you’re looking at published books, but how do you know where to put the page cuts in a manuscript that you’re working on? This can be done by looking for those moments in the text with a sudden scene change. Think of them as ‘3… 2 … 1 …’ moments, or points where someone reading aloud will add a lot more drama. For instance, consider where you might want page turns with the following sentences:

The little owl stepped up to the edge of the branch, puffed up its chest, stretched out its wings and leapt into the air. What a glorious feeling! it thought, just before it started to fall down … down … down … and then … CRASH! landed right in the middle of a bluebird nest.

Bear in mind that picture book pacing also means considering how many words are on each page. Effective page turns can mean that a page with a big reveal or sudden dramatic moment might have just a few words – or even no words at all. While there are many ways to split up a moment like this, an option could be:

(Spread 1 – left page)

The little owl stepped up to the edge of the branch, puffed up its chest, stretched out its wings and leapt into the air.

[illustration: full page of baby owl preparing to fly]

(Spread 1 – right page)

What a glorious feeling! it thought, just before it started to fall down … down … down … and then …

[illustration: page of vignettes showing owl at various stages: 1) happily flying, 2) realising it’s falling, 3) falling more, 4) properly tumbling down]

(Spread 2 – full spread)

CRASH! landed right in the middle of a bluebird nest.

[illustration: full spread of a dishevelled owl sitting unhappily among some perplexed bluebird chicks]

This is an exaggerated way to write this out in a manuscript and is rarely necessary, but it is sometimes helpful if a self-publishing author needs to commission the illustrations according to the page splits (because it will influence what the illustrator is commissioned to draw and how many illustrations are required). When working with authors who plan to submit the book to agents or publishers, then it’s better not to be as prescriptive with page numbers or illustrations, and to simply leave line breaks within the text to give an indication of pacing.

So if you’re getting into picture book editing, remember that there’s more to it than just the text and illustrations – there’s also the whole format of the book that you can play around with. That’s what makes editing picture books both challenging and exceptionally fun!

About Lisa Davis

Lisa Davis (she/her) is a children’s book editor and publishing consultant who specialises in making children’s books more inclusive. She has worked at major publishers in the UK including Simon & Schuster and Hachette, and in departments including editorial, rights and production. Before going freelance in 2018, she was the book purchasing manager for BookTrust, the UK’s largest children’s reading charity, which gives over 3.5 million books a year directly to children.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: child reading by Marta Wave on Pexels; Rosie’s Walk and Nine Lives Newton, Simon and Schuster.

Posted by Sue McLoughlin, blog assistant.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.