By Robin Black

Working in the shadows of nearly every project, editors could do with a bit more public understanding. ‘We don’t have much of a budget,’ invokes the client, though I wonder about companies that don’t have the budget to be good. Who sets a budget to be bad?

Working in the shadows of nearly every project, editors could do with a bit more public understanding. ‘We don’t have much of a budget,’ invokes the client, though I wonder about companies that don’t have the budget to be good. Who sets a budget to be bad?

Show me a copy-editor and I’ll show you a living combination of robust general knowledge, an eye for detail that won’t quit, and a flair for the metaphysical. (You try rearranging the words so readers are visibly moved by the end.) Do you care that your editor detects that a particular adjective can make two appearances in a single chapter but not three or four? Either way, you should absorb the manuscript, whether it’s a white paper, a website or a manual, without tripping over such infelicities. In that sense, you should forget about us.

But not so much that we’re taken for granted when it comes time to employ our services. I’m uncomfortable about driving home the point, however: surely there’s scarcely a métier out there whose adherents don’t feel misunderstood and underappreciated from time to time? Lawyers, for example, lament that they could do more to help if only they were consulted before things go haywire. The stewards of the Southwark Household Reuse and Recycling Centre, where a maze of conveyor belts criss-cross in improbable fashion, aren’t asking you to rinse out your discarded materials for their health; it gums up the system, slowing down the work of nearly everyone on the premises. And in the face of a public that doesn’t listen, the distinct burdens of climate scientists weigh heavily: armed as they are with the science that impinges on you and you and you, they can scarcely daydream about escaping to New Zealand any more. (A desperately hungry populace tends not to care overly about property rights.)

It is with gentle misgivings about self-centredness, then, that I invite you to turn your attention expressly to editors, for whom the information imbalance translates into high demands for humble pay. I self-select out of some of the worst of it by rejecting low-paid jobs and seeking out the clients who feel as I do about a job really well done. And while quality is its own reward, equally, someone out there wants to pay for that quality, and my idealistic mind aims to keep finding them.

But then my sister called. Her website needed some tidying up, and she’s a pragmatist: ‘Let’s just do what we can in the time we’re given and get this crap out the door.’ So much for my idealistic mind, I thought. I demurred, and she rolled her eyes and politely dropped it.

Should I have just sidestepped my standards and been helpful? For the answer, I look to the guiding principle of 28th annual SfEP conference: ‘It depends.’ When newbies jump on the forum to ask for feedback on their websites, I may steel myself ahead of reading those threads because the general positivity of our members, which I laud and cherish, means the critiques veer towards the reliably panegyric instead of the helpfully critical.

I’m quite unsure whether that’s a bad thing, however, though I admit to a little frustration, and indirectly it has to do with money.

Ugh, money. I’m one of those people who is uncomfortable talking about it, likely to my own detriment, so let’s get this over with: the choice I make not to list my rates on my website – I never discuss fees until the client expresses an interest in hiring me – maps onto the editor and business person that I am. My approach is to psychologically leverage clients with my chat, my bearing and my materials, only to strike with a generous payment suggestion once the iron is hot. But such wiles could go awry in the absence of the rest of me – which is to say that my approach comes off naturally and therefore honestly from me, but grafting it onto you is iffy.

For me to insist that you should never publish your fees on your website is glib, and besides, look at all those lovely, experienced editors telling you something different. I throw up my hands in friendly defeat, satisfied that everyone is acting in good faith as they post disparate advice, and I stay quiet.

And yet. There is an assumption among our members, which I share, that we concentrate on doing a very good job while employers exploit us with low fees and outsized projects at capped rates. Leaving aside my contention that no one should be taking lower than the CIEP’s suggested minimum rates (Glib? But I stand by it), I put to you this question: why would a client pay you professional rates when you’ve got an amateur public face? When clients move forward with unedited or poorly edited materials, as is their wont, how long can you stay indignant when your own website is untouched by proper design and typography?

We prize words over images, but our Venn diagrams may or may not overlap with those of potential clients, so see it through their eyes, and subdue your inclination to tell them everything! that! you! do! well! As editors toil in the shadows and the public neglects to recognise the metaphysical power we wield boosting human connection through communication, nearly everyone appreciates a professionally rendered website. It makes budget holders relax.

We prize words over images, but our Venn diagrams may or may not overlap with those of potential clients, so see it through their eyes, and subdue your inclination to tell them everything! that! you! do! well! As editors toil in the shadows and the public neglects to recognise the metaphysical power we wield boosting human connection through communication, nearly everyone appreciates a professionally rendered website. It makes budget holders relax.

Allow me to be mercenary for another moment: if you want to be paid properly as a professional editor, by clients with robust budgets, then hire a professional to craft your website. And for Heaven’s sake don’t talk them down in price if you want to be extended the same courtesy.

Look, the things I’m doing wrong with my own sole proprietorship are legion. In business, you can’t do it all; there’s always something more you should be doing. And that’s not advice; I’m trying to tell you it’s a trap. In his wisdom, Oliver Burkeman warns us that ‘getting it all done is an illusion. You’ll never get to the summit of that mountain because the climb goes on forever’. Consider the editors who do quite well, thank you, with no website at all or an online offering barely a step up from GeoCities chic.

Being a capable editor – doing the work well – is more important in my mind than having a professional website anyway. I view with mistrust careers that coast on marketing and talking instead of execution and elbow grease, but I would say that, wouldn’t I? Execution and elbow grease is what I know how to do! Persuading people to buy things they don’t initially want or fundamentally need embarrasses me, which means that my own self-marketing is lacklustre.

As for my sister’s website, months later I relented, agreeing to help if and only if we could start small, rendering good text and better design choices with a one-page website that tacitly communicates to visitors that they’ve landed where quality matters.

We should tell her story, I insisted, bringing her role out of the shadows … um, relaying the underlying, human aspects of her profession for clients … or something like that. Wait: What is it you do again, Stephanie?

Pfft. There goes the public again, scarcely taking the time to understand.

A financier and editor-who-does-it-for-love, Robin Black believes that no profession or livelihood will escape without integrating the climate crisis into its day-to-day, and he finds writing about himself even more embarrassing in an era of existential threat. Bravery is called for, however, so he manages it here.

A financier and editor-who-does-it-for-love, Robin Black believes that no profession or livelihood will escape without integrating the climate crisis into its day-to-day, and he finds writing about himself even more embarrassing in an era of existential threat. Bravery is called for, however, so he manages it here.

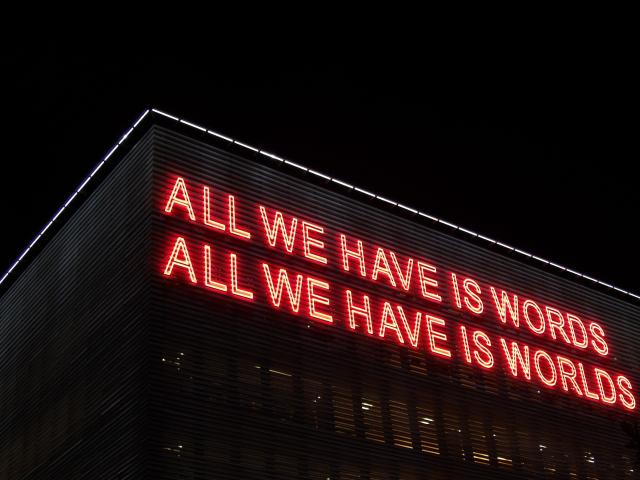

Photo credits: For hire – Clem Onojeghuo; All we have is words – Alexandra, both on Unsplash

Proofread by Andrew Macdonald Powney, Entry-Level Member.

Posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.

I am grateful you decided to contribute to my new branding as I know your standards are high. I think the look and feel is great and shares a story that, hopefully, empowers others to share their story.

Thanks, Robin. You put it well.

An interesting read, Robin, and thanks for the link to Mother Jones (yet another website I wish I’d known about before).

In the bio, “Robin Black believes that no profession …” I’m trying to figure out what “integrating the climate crisis” means for editing as a profession. Not to appear glib, but do you mean on a daily basis we should use less paper? Or should we be volunteering editorial services to people writing about the climate crisis? I mean, we can all make individual changes, but as a profession what do you suggest?

Changing behaviours by merely asking people to change, or even warning them, is frequently too much of a deep uphill battle depending on one’s personal psychology, and for this challenge we need everybody.

Changing norms, however … So as an organisation we formally and informally create the spaces for our members to discuss and examine the climate emergency, signalling to each other and then to other organisations that our attention is on it. ‘There is no job that does not connect to sustainability,’ writes my IPCC-report-author uncle, ‘and every job will require people who understand these connections.’

I realise this is a little abstract – and as an aside, I submit that your question, Riffat, is just the sort of preliminary thinking/action/baby step that sends us in the right direction – so here are two rather concrete suggestions:

1) We publish the names of thirty companies that will keep making money with activity that hastens our environmental demise, publicly declaring as an organisation that we recommend our members look elsewhere to sling their trade. I don’t care if people laugh at us because we’re small.

2) We do a three-to-five-page internal comms ‘report’, using the nifty skills of our membership in design, writing, typography, storytelling and editing, which relates how the membership feels about the climate crisis, whatever those thoughts are. That way, we bring the story more alive for ourselves and share our anxieties and hopes. This is rich ground, and my mind swims with the possibilities for interviewing and highlighting our membership’s feelings, nail-biting, jokes, guidance and stoicism about it all.