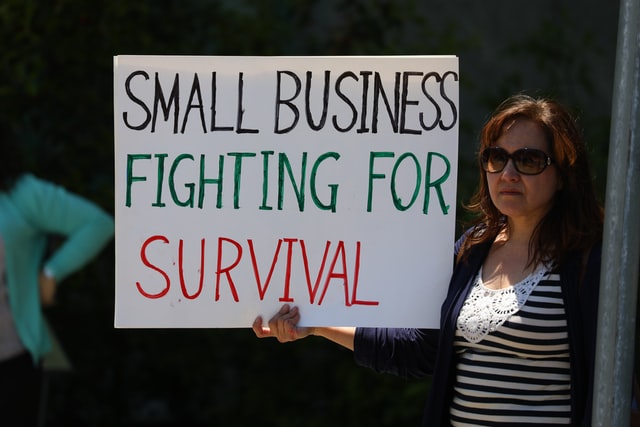

In this post, Louise Bolotin* talks about her experience of trying to revive her editing business after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic wiped out her work.

Like many freelancers, I was hit hard by the pandemic. 2020 started well enough, including a huge two-month project for a Commission. But in the week before we went into lockdown last March, I ran into deep trouble. First, as businesses battened down their financial hatches, all the projects I’d had booked in up to mid-June were cancelled by my clients. And then the local weekly newspaper where I’d worked as their subeditor for several years rang to say they were laying me off. In the space of a few days, I lost 100% of my work. Utter despair and panic set in because after the final week of that lucrative Commission job, I had nothing – for the first time in 15 years of working for myself.

Normally I’d never admit this, but I was not alone. I heard countless similar tales from other freelancers. For a few weeks I seriously contemplated getting a supermarket job. I had bills to pay, after all. I even got as far as half-heartedly filling out some of an application form for one supermarket. But I reminded myself that I still wanted to be my own boss, rather than someone’s employee. So as the public clamoured to ‘build back better’, I resolved to do the same, as there was no point dwelling on what I’d lost.

Once the shock had settled, it was time to roll up my sleeves. Under lockdown, I had plenty of time to review what I needed to do to bring work back to me – I’d let a few things slide for a while because when you are busy you’re often too busy to do marketing essentials. I also thought about what I didn’t want so I could make the big decisions. One thing I definitely didn’t want was to commute again. I’d worked at the newspaper one day a week, sometimes two, but the prospect of sitting on a train for 45 minutes each way in the middle of a pandemic was now unthinkable.

Despite the prospect of no income for goodness knows how long, I pledged to do a minimum two things every day that might generate work, and I also felt I could afford to spend a bit to earn a bit as I qualified for the government’s SEISS grant.

First, it was time to invest in a new website and logo. My then website was 10 years old and looked dated and unprofessional. Within a few weeks of launching my new look, my site analytics were showing increased visits and enquiries.

Next, it was time to up my CPD. First in my sights was the CIEP’s Medical Editing course, something I’d planned to do for a while but not got round to. Under lockdown I had time to get cracking. I completed the course in October and then paid for a freelance directory entry on a specialist network with the aim of finding medcomms work. That is starting to pay off.

As a member of the National Union of Journalists I have access to a huge suite of free courses run by the Federation of Entertainment Unions. In April I joined their webinars on Cash Flow Planning and Freelance Finance to get a quick grip on loss of income. These helped ease some of the financial stress I was experiencing. I also did the FEU’s Grow Your Business via Email Marketing webinar in August – it was both useful and inspiring. Within days I’d opened a Mailchimp account and am now sending a monthly newsletter to my clients. Late last year, I attended the FEU’s course on goal-setting. I’d never done this before, but I set two goals for this year and I’m reviewing them every month. One was to find three new long-term contracts – two of them found me in December.

There were other things – signing up to some paid-for freelancing newsletters that signpost work opportunities and yet more webinars, and joining a Slack community for journalists that was hugely valuable in providing camaraderie and support for lockdown stress and mental health.

Among my ‘two things a day’ pledge, this was a good time to update my various directory entries, including my CIEP one. I polished my CV and opted to spend more time on LinkedIn engaging with colleagues. I scoured job sites most days to look for freelance work. I got commissioned by a national newspaper to write a feature on being separated from my husband under lockdown. My NUJ branch also hired me to update my training courses on the business of freelancing and run them for branch members on Zoom.

The hard labour paid off and work has come back – in November I was fully booked for the first time since lockdown. And I learned the following:

Resilience matters: I’ve always been strong, and have bounced back from some of my life’s most challenging situations. I drew on that in 2020 to rebuild my business, bank balance and sanity. Never underestimate the power of keeping going – you’ll get to where you want to be eventually.

Envy is pointless: I felt irrationally furious at some colleagues who were still busy. Why them? Why not me? Especially the ones who’d only just started freelancing. But who knew what trouble they too might be in? For all I knew, just because they seemed busy, it didn’t mean they too weren’t struggling. I felt better when I let go of the envy and focused on building back.

It’s OK to ask for help: I’m not great at this, but I did. I was honest on social media, in the forums of my professional bodies and to friends offline about being in a hole and needing work. This helped keep my spirits up and some CIEP colleagues were kind enough to put work my way. I have since given interviews on how freelancers were hit and what I did to get back on my feet. I hope that helped others.

*Louise Bolotin died in October 2022; her contributions are much missed.

About Louise Bolotin

Louise Bolotin began her career in journalism, turning her attention to the editorial side after a decade. She still writes occasionally, but has been a freelance editor since 2005 and is an Advanced Professional Member of the CIEP. She specialises in working with companies on business documents, alongside copyediting a few books every year. An NUJ trainer on the business aspects of freelancing, she took her own advice when the pandemic struck.

Louise Bolotin began her career in journalism, turning her attention to the editorial side after a decade. She still writes occasionally, but has been a freelance editor since 2005 and is an Advanced Professional Member of the CIEP. She specialises in working with companies on business documents, alongside copyediting a few books every year. An NUJ trainer on the business aspects of freelancing, she took her own advice when the pandemic struck.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: empty train by Carl Nenzen Loven; small business fighting for survival by Gene Gallin on Unsplash

Posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.