Three CIEP members, Kia Thomas, Judith Leask and Eleanor Abraham, reflect on the self-publishing process from their perspectives as author, editor and typesetter.

Kia: the author

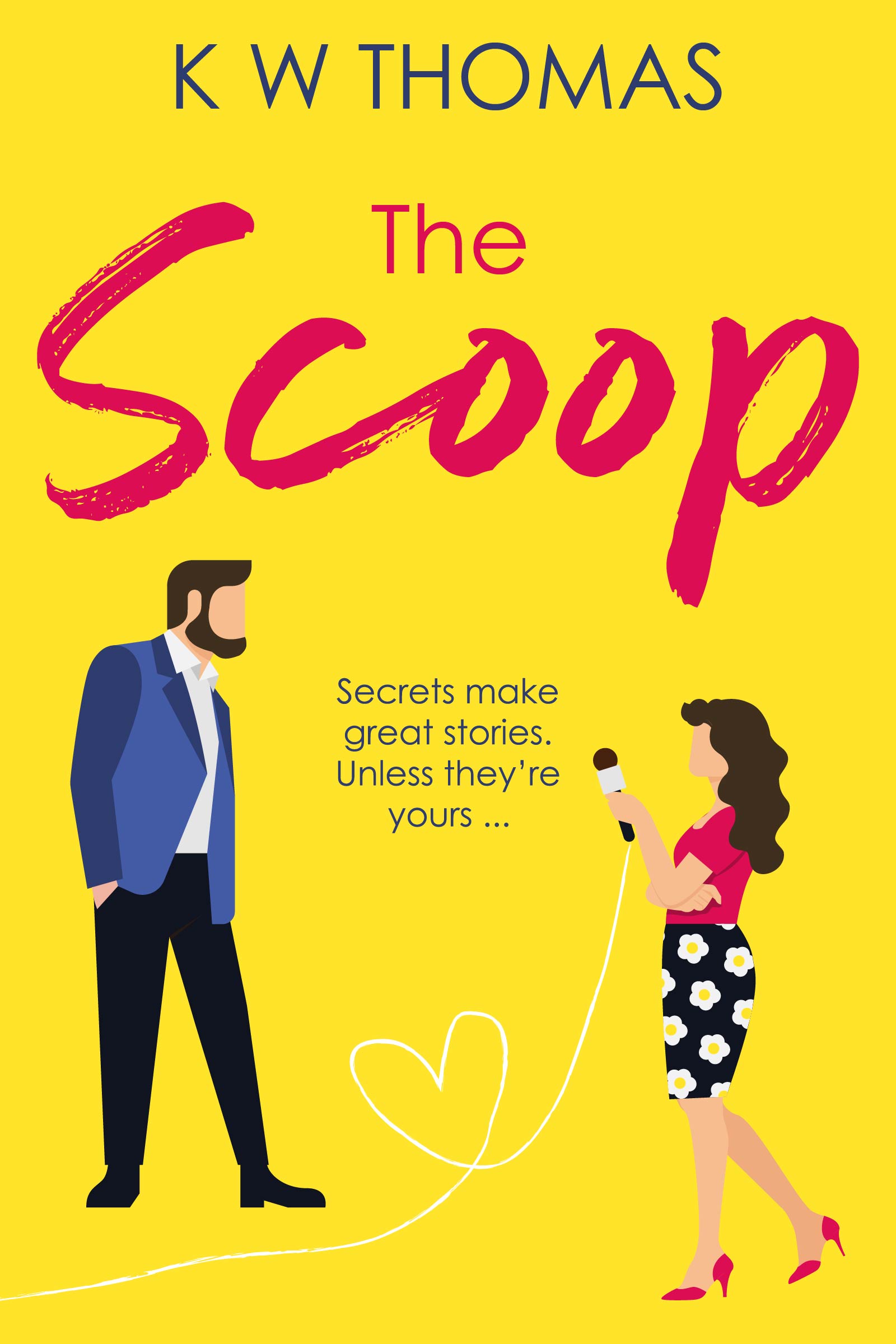

I self-published my first full-length novel, a contemporary romance called The Scoop, in July 2022. I always knew I’d hire a professional editor before I published it (practise what you preach and all that), and I always knew I’d start my search within the CIEP, whose members have been as wonderfully supportive of my publishing journey as they’ve been on my editing one.

Finding the right editor

It was important to me to find not just a good editor, but the right one for me. I wanted someone I could trust, someone who was fun to work with, someone who could work with me the way I am – as an editor, I’m generally quite hands-on, and I work best with people who are willing to put their trust in what can sometimes be a lot of intervention. But I’m not that kind of author – I’m the absolute pain in the backside who’s extremely precious about every last one of her wo rds. (One of my notes to my editor was ‘You can prise my adverbs out of my extremely cold, absolutely dead hands.’)

rds. (One of my notes to my editor was ‘You can prise my adverbs out of my extremely cold, absolutely dead hands.’)

I began by asking CIEP members who were looking for more experience in fiction to put themselves forward for the job. Fiction editing is very competitive, and various CIEP members have helped me find opportunities over the years, so I wanted to offer that chance to someone else. I asked each candidate to complete a sample edit. There are often debates in editorial circles about whether they’re a good idea or not, and whether editors should offer them for free or not, but I know that I wouldn’t have been able to hire someone without seeing their work, as every editor is so different.

And this was proved by the ways in which each editor approached the text. No two samples were exactly the same – everyone picked up on slightly different things, and had different solutions for the problems they identified. That said, every single editor did point out one ambiguous passage that was totally clear in my mind, and it hadn’t occurred to me until then that it could be read differently. It just goes to show why external editing is so important, for everyone; I might be a professional editor, but I’m still the author who can’t see the story from that objective angle, because I’ll always know what I meant!

I found some great editors through this process, and in the end, I chose to work with Judith Leask. Her sample showed me that she had a really sharp eye, which is obviously important, and she could work with my ideal timeframe and budget. And, just as importantly, her queries had a warm, friendly tone, which was exactly what I was looking for in my relationship with my editor.

The editing process

The edit itself was great – Judith picked up on so many little quirks I didn’t know I had. It was a really (one of my quirks is that I am far too in love with this word, I’ve discovered) positive experience, and at the same time humbling – being edited definitely makes me a more empathetic editor. She did a great job and made so many suggestions that made my story better, but at the same time always respected that the final decisions were mine to make. (I did end up ignoring many of her perfectly valid suggestions – like I said, I’m precious!)

Working with a typesetter

Once my manuscript had been copyedited, it was time to prepare it for publication. I’d worked with Eleanor Abraham before on A Very Sweary Dictionary, so working with her again was an easy decision. Design was more important for the dictionary, but even though a novel’s requirements are much simpler, I still wanted a high-quality interior. I’m a total pain when it comes to anything visual because I only know what I don’t want, but Eleanor was endlessly patient and happy to tweak things until I was satisfied.

I’m so happy with the finished book – it’s a polished, professional product that I’m proud to be sharing with the world.

Judith: the editor

Being chosen by Kia to edit her novel was very exciting, because I knew I’d learn a huge amount from her, and that turned out to be true.

I’ve never minded being asked to do a sample edit, as it’s part of the process for both parties to get to know one another, and it can help with producing an estimate of timing and costs. I see it as an opportunity to show how I’ll be able to add value to the author’s work, and hopefully that I’ll be reasonable and friendly at the same time. I want the author to feel reassured that they’ll keep control of their work. I’m so glad Kia’s response was so warm and encouraging.

It was both easy and hard to work with an Advanced Professional Member (APM) of the CIEP – easy, because Kia knew exactly how she wanted the process to work; and hard, because it was sometimes difficult to find anything to edit! But I really appreciated that Kia had already made some style choices that I could add to my style sheet before getting started, and she let me know when she’d prefer a query without an edit, and where it would be OK to dive in (potentially with a comment). I wouldn’t expect an inexperienced author to be able to give those instructions, but I’d make sure they knew they’d retain control.

Keeping the author’s voice

I was happy to accommodate Kia’s love of adverbs (I might have worked on a few of the instances of ‘really’!). Her use of adverbs just seemed to work for her characters’ voices and for her close narrator’s voice, giving them a fun, informal and modern feel. I didn’t feel the need to suggest a more interesting use of vocabulary, which I sometimes do when I see adverbs. And this point illustrates what I love about editing – it feels like part of the creative process and an accomplished craft. It navigates various factors and focuses on working with the author to make the work consistent and right for their style and intended audience, while keeping an eye on the conventions (there are far fewer rules than you might think).

In some places, my main input to Kia’s book was to consider repetition of words or sentence structures. I made suggestions for alternative words or phrasing, and for some Kia gently gave feedback that she didn’t feel they were in keeping with her voice. I’m completely happy with what she describes as a controlling approach, because I’m always clear that all decisions ultimately lie with the author. We had a laugh about one or two of the repeated words in certain, ahem, intimate scenes. I’ll leave it to your imagination which words those might have been!

Making conscious choices

I also kept in mind the need for sensitivity and conscious language choices, but (as you might expect from a professional editor) Kia had written with these things in mind. I made one comment relating to the female character’s safety, but Kia decided the plot wouldn’t allow a different choice, which was a completely understandable decision. I’d done my job, though, in making sure an author is making their choices consciously.

Where Kia decided she didn’t want to go with a suggestion of mine, just because her wording felt right to her, I quite understood. I know what that’s like, and I don’t take it as a snub. I’d make a comment to an author if I felt there was a risk in their choice, but that didn’t apply here, and authors are free to disagree if they wish.

I have to say I haven’t had a bad experience working with an independent author. I’ve always found authors to be open to the input from a professional editor and happy to see what a fresh pair of eyes will spot.

I think Kia’s book will be successful, because she’s written a truly entertaining novel that just about anyone would enjoy. If she’d told me to stop work after a few chapters, I’d have bought the book and read the rest anyway.

Eleanor: the typesetter

Kia seems to think she was difficult, but I didn’t think that. She made it clear she likes things plain and simple. That’s sometimes all the brief you’re going to get from a client. I find that preferable to receiving a brief that is very prescriptive. Sometimes if people have really specific requests, maybe without understanding the repercussions of those, it can result in some time-consuming discussions. I suggested a few fancier features to her, knowing she’d likely say no, but it was useful to see what she considered to be plain enough. Rather than her being picky, I thought she was quite pragmatic about accepting advice when it mattered.

Working as a team

A pragmatic and professional attitude is common with the indie writers and publishers I work with as an editor and typesetter. I enjoy working with people who have clear goals for their books, brand and business. They take selling books seriously and consider the publishing professionals working with them as an essential part of the team, rather than an expensive extra.

Self-publishing can be an overwhelming process. For some writers, it makes sense to outsource certain tasks so they can concentrate on the creative stuff … and on the sales and marketing, which are going to take up lots of time and effort.

Typesetting, like proofreading, is a process that people often assume is quite easy and for that reason they might choose to do it themselves. Making print attractive and readable, while conforming to the conventions that make it printable, is, like most things, trickier than it looks. But then, I would say that.

The typesetting process

For Kia’s layout I imported her edited Word file into Adobe InDesign. In my opinion, it’s the best tool for the job. Cheaper alternatives have just eaten up my time working around their limitations. I can control and automate a lot of InDesign’s layout settings (running heads, hyphenation, word breaks, styles, kerning, table of contents etc) but I do what I call a quality control (QC) check too. If no further proofreading is going to take place (and these days that stage has usually been carried out in Word), this QC check is the equivalent of the layout checks a proofreader would do (checking that the way the text appears on the page is attractive, balanced and as it should be).

Although my settings choices took care of ‘widows and orphans’ (short lines or single words that end up at the top or bottom of a page), and kept bad breaks to a minimum, my own clearly prudish settings kicked in one time to prevent the first word on a page being ‘nipples’.

After typesetting, I sent Kia a PDF proof and she marked up any final changes she wanted with Acrobat commenting tools. With final corrections done, we exported an ePub from the InDesign file. Other ebook formatters may work in a different way but that’s the workflow and software that I prefer.

Working with another CIEP editor was a great experience. We trust each other and speak the same publishing language, and no doubt this contributed to the process going fairly smoothly. It also helps when you find people to work with who are good-humoured and pleasant!

Kia

Working with such helpful, friendly professionals was an important and really positive part of my self-publishing journey. It cost money, true, and I may never make that back (because I’m terrible at marketing), but my writing is absolutely worth investing in. I’m looking forward to working with my fantastic little team again for book 2!

About Kia Thomas

Kia Thomas is an Advanced Professional Member of the CIEP who works primarily with independent authors, specialising in contemporary romance. She is also the author of A Very Sweary Dictionary, a style guide for bad language; Wings, a literary fiction novelette; and, as KW Thomas, The Scoop, a contemporary romance novel.

Kia Thomas is an Advanced Professional Member of the CIEP who works primarily with independent authors, specialising in contemporary romance. She is also the author of A Very Sweary Dictionary, a style guide for bad language; Wings, a literary fiction novelette; and, as KW Thomas, The Scoop, a contemporary romance novel.

About Judith Leask

Judith Leask came to freelance editing following eight years of honing her skills in creative writing, and twenty years’ writing experience in the business and public sectors. Now a passionate copyeditor and developmental editor for fiction and narrative non-fiction, she is an Intermediate Member of the CIEP.

Judith Leask came to freelance editing following eight years of honing her skills in creative writing, and twenty years’ writing experience in the business and public sectors. Now a passionate copyeditor and developmental editor for fiction and narrative non-fiction, she is an Intermediate Member of the CIEP.

About Eleanor Abraham

Eleanor Abraham has been an editor and typesetter for a long time and remembers having to look stuff up in encyclopaedias, paste up camera-ready-copy and send faxes. She will bore you about typography at the drop of a descender. Her published written words can be found in Meowditation, Maw Broon’s Cookbook, Maw Broon’s But an’ Ben Cookbook and Maw Broon’s Afternoon Tea Book. She is an unapologetic generalist – from computer science to memoir – but loves a cosy whodunnit on a rainy afternoon.

Eleanor Abraham has been an editor and typesetter for a long time and remembers having to look stuff up in encyclopaedias, paste up camera-ready-copy and send faxes. She will bore you about typography at the drop of a descender. Her published written words can be found in Meowditation, Maw Broon’s Cookbook, Maw Broon’s But an’ Ben Cookbook and Maw Broon’s Afternoon Tea Book. She is an unapologetic generalist – from computer science to memoir – but loves a cosy whodunnit on a rainy afternoon.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: header image by Ciao on Pexels, woman working on a laptop by Teona Swift on Pexels, wooden typesetting blocks by Raphael Schaller on Unsplash.

Posted by Eleanor Smith, blog assistant.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP