Do you go cold when you hear the words ‘dangling participle’? Does the mere mention of a comma splice or a tautology make you anxious? Do you have a faint memory, perhaps from primary school, that people who write ‘proper’ English never start a sentence with ‘And’ or ‘But’? Perhaps you’ve been flummoxed by the terms used in the school materials that you’ve had to work with while homeschooling your children (you are not alone: see this article by the former Children’s Laureate Michael Rosen).

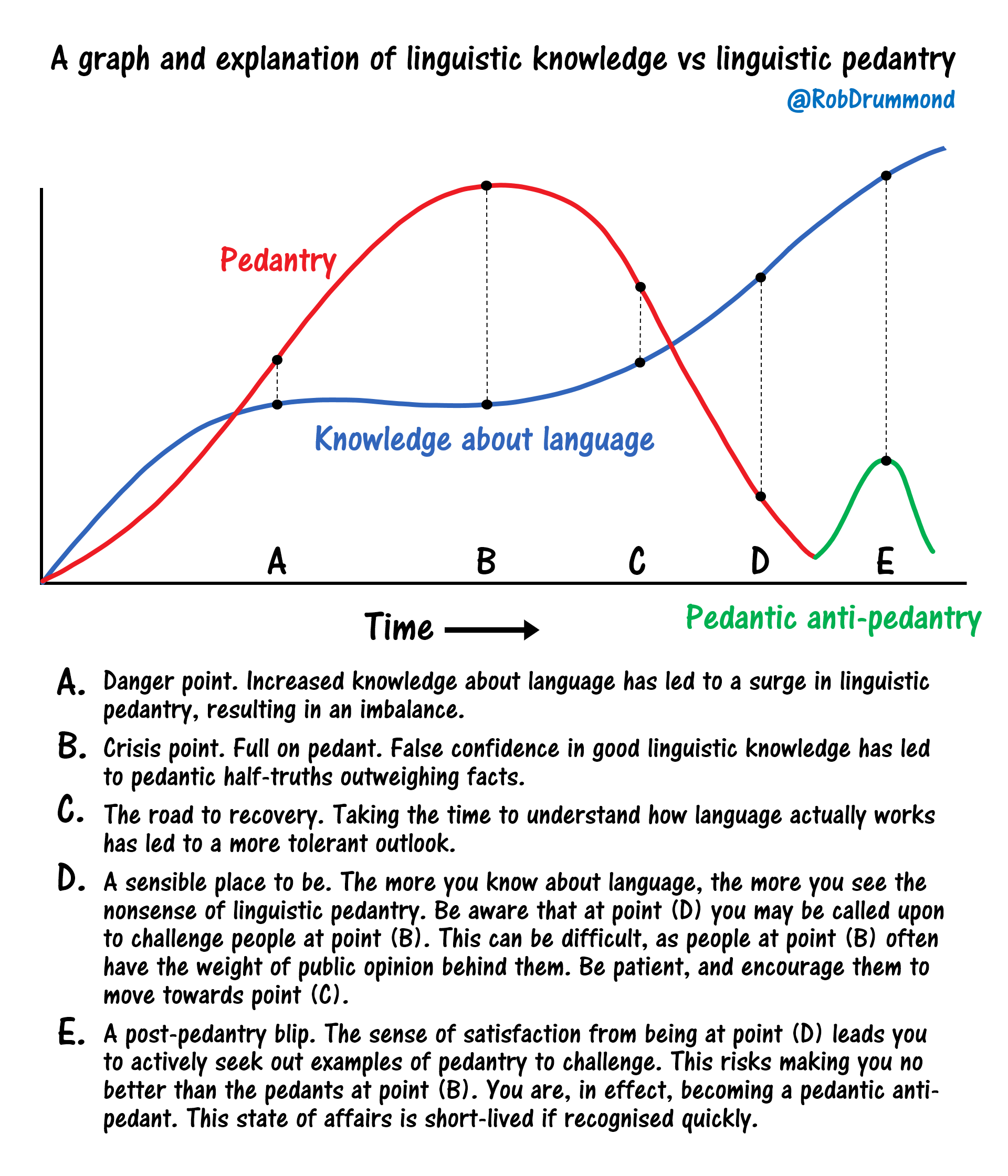

Actually, you almost certainly know much more about grammar and punctuation than you realise. The ‘rules’ are often no more than old-fashioned preferences or prejudice, and may not be relevant anyway. It all depends on the text: a novel for young adults, an information leaflet for patients at a doctor’s surgery, or an annual report for a major company – each requires a very different approach. The tone in which the document is written, and the intended readership, will dictate how strictly grammar and punctuation rules should be applied.

Actually, you almost certainly know much more about grammar and punctuation than you realise. The ‘rules’ are often no more than old-fashioned preferences or prejudice, and may not be relevant anyway. It all depends on the text: a novel for young adults, an information leaflet for patients at a doctor’s surgery, or an annual report for a major company – each requires a very different approach. The tone in which the document is written, and the intended readership, will dictate how strictly grammar and punctuation rules should be applied.

If you work with words, in any capacity, and you feel that your knowledge could do with a brush-up, then the new online course from CIEP, Getting to Grips with Grammar and Punctuation, could be just what you need.

Why both grammar and punctuation?

Let’s see how the Collins Dictionary defines grammar: ‘the ways that words can be put together in order to make sentences’. It defines punctuation as ‘the use of symbols such as full stops or periods, commas, or question marks to divide written words into sentences and clauses’.

This explains why these two subjects have to go hand in hand. Grammar is about putting words together; punctuation helps the reader to make sense of those words in the order in which they have been presented. Used well, the grammar and punctuation chosen should be almost imperceptible, so that nothing comes between the reader and the text. If they are used poorly, the reader will be confused, may have to go back over sentences as they puzzle out the meaning, and may eventually stop reading as it’s just too hard to figure out.

For the want of a comma …

Take this well-known example. ‘Let’s eat, Grandma’ is a friendly invitation for Granny to join the family meal. If you remove that tiny comma, the poor woman is at the mercy of her cannibal grandchildren.

More seriously, a misplaced comma can have huge legal and financial implications (see ‘The comma that cost a million dollars’ from the New York Times).

Poor grammar can have unintentional comic effects (dangling participles are particularly good for this, as you can see here). It could even affect your love life (see this Guardian article ‘Dating disasters: Why bad grammar could stop you finding love online’).

So it’s worth knowing the rules you must follow, and those that can sometimes be ignored.

Why this course?

Why this course?

Getting to Grips with Grammar and Punctuation is for anyone who works with words. It aims to:

- clarify the basic rules of English grammar

- clarify the rules of English punctuation

- discuss some finer points of usage and misusage

- explain the contexts in which rules should or need not be applied.

This course alternates units on grammar and punctuation, with two basic units followed by two that go into more detail. Each unit has several sets of short, light-hearted exercises on which you can test yourself to see how well you have taken in the information. The penultimate unit discusses finer points of usage, and finally, there are three longer exercises on which to practise everything you’ve learned from the course. There is no final assessment for the course, but every student is assigned a tutor and is encouraged to ask for their help if any questions arise as they work through it.

There is an extensive glossary of grammatical terms as well as a list of resources, in print and online, for further study. This includes a number of entertaining and opinionated books on grammar which will prove, if nothing else, that even the pundits don’t always agree.

By the end of this course, you should have a clear idea of some of the finer points (and many of the pitfalls) of English grammar and punctuation. You should have developed some sensitivity to potential errors, acquired greater confidence, and learned strategies to make any written work you deal with clearer, more effective, more appropriate and even, perhaps, more elegant. And we hope that you will have found it interesting and entertaining at the same time.

Annie Jackson has been an editor for longer than she cares to admit. She tutors several CIEP courses and was one of the team who wrote the new grammar course. Despite many years wrestling with authors’ language, and before that a classics degree, she realises there’s always something new to learn about grammar.

Annie Jackson has been an editor for longer than she cares to admit. She tutors several CIEP courses and was one of the team who wrote the new grammar course. Despite many years wrestling with authors’ language, and before that a classics degree, she realises there’s always something new to learn about grammar.

With thanks to the other members of the course team who contributed to this post.

Photo credits: books by Clarissa Watson on Unsplash

Posted by Abi Saffrey, CIEP blog coordinator.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.