Capitals for some words, lowercase for others, and what exactly is a preposition anyway? Cathy Tingle tries to navigate the nuances of title case in headings, and in the process discovers the importance of editorial judgement.

At the end of October 2021’s A Finer Point we were running breathlessly away from the surprisingly complicated zone of sentence case, with its proper noun, identity and emphasis landmarks, towards what we were hoping would be the more straightforward domain of title case. And, four months later, we’re finally here (quite a long run, that). Let’s take a look around.

Getting our bearings

It’s tricky to know what to call this place, as it has many names: maximal capitalisation, initial caps, title case, headline style, smart capitals.

Ah, well. Even if we can’t settle on a label, it should be fairly easy to identify the characteristics of the style. Let’s consult good old New Hart’s Rules on what it calls ‘maximal capitalization’. It says to capitalise ‘the first letter of the first word and of all other important words’. Hang on a minute – what does ‘important’ even mean? Don’t panic: Hart’s has a list.

Nouns, adjectives (other than possessives), and verbs are usually given capitals; pronouns and adverbs may or may not be capitalized; articles, conjunctions, and prepositions are usually left uncapitalized.

Oh. That’s two usuallys and a may or may not. Which suggests very strongly to me, friends, that where we are, in fact, is in the vast realm of editorial judgement.

How can we possibly hope to get our bearings, then, when it comes to title case? Well, let’s start by hanging on to something that at least appears solid by trying to identify what’s never capitalised – or pretty much never.

What not to capitalise

Right then, in general, unless they are the first word in the title don’t capitalise the following word types:

- Articles: a, an, the.

- Conjunctions: joining words, for example and, or, but, for, so.

- Prepositions: words that express a relation to something, for example on, off, of, to, by.

Sounds simple. But actually it’s not. It’s with prepositions in particular that we run into difficulty, because they’re not all nice and short like the ones listed above. Some, like beneath, between, against, around, towards and within are much longer, and would look odd uncapitalised. Which is partly why some style guides have a rule that all words of four letters and longer should be capitalised. For others it’s five letters or longer. Chicago style, bravely (or perhaps with a certain unfussy genius) advises lowercase for all prepositions, regardless of length. Let’s see what Benjamin Dreyer, in Dreyer’s English, has to say about that:

If you say ‘prepositions are invariably to be lowercased’, as some indeed say, you’re going to be up against titles like Seven against Thebes or I Served alongside Rommel, and that certainly won’t do. The cleverer people endorse lowercasing the shorter prepositions, of which there are many, including ‘at’, ‘but’, ‘by’, ‘from’, ‘into’, ‘of’, ‘to’, and ‘with’, and capping the longer ones, like ‘despite’, ‘during’, and ‘towards’. I’ll admit that the four-letter prepositions can cause puzzlement – I’d certainly never cap ‘with’, but a lowercase ‘over’ can look a little under-respected.

Ah, sometimes capping a four-letter preposition, and sometimes not. Interesting and confusing at once.

But – and it’s a big but

To add to the intrigue, Dreyer then addresses but. I’ve listed it in the previous section as a conjunction, but, unfortunately for us, it is so much more. In fact, but is:

- a conjunction (‘Yes, but no’)

- a preposition (‘Everyone was using sentence case but me’)

- an adverb (‘We are but four sections from the end of the article, so hang in there’)

- or a noun (‘But – and it’s a big but’, although that phrase always makes my 9-year-old son chortle, as if the second but, the noun, is furnished with an extra t. (Eye roll.) If you’d prefer a less snigger-triggering example, Dreyer gives ‘no ifs or buts about it’.)

But is only one of many words that fit into various word-type categories. There are also, as Dreyer points out, such things as phrasal verbs, which are likely to contain a word you’d usually lowercase (‘Oh, Come On!’ we might shout back exasperatedly, if it were possible to shout in title case).

What to capitalise

Before we bid farewell to Benjamin Dreyer for now, we must note that he would always capitalise the last word, as well as the first word, of a heading in title case, as would Amy Einsohn and Marilyn Schwartz, authors of The Copyeditor’s Handbook, which contains an excellent section on headline style. Predictably, this isn’t a universal rule.

However, capitalising nouns, adjectives and verbs in title case is pretty much a sure thing. As this should be fairly self-explanatory it’s only left to me to remind you that ‘be’ and ‘is’, though small words, are verbs and should always be capitalised … ah, unless in exceptional cases, such as those outlined in a recent CMOS Shop Talk article which explored whether ‘Is’ should always be capitalised in titles, or to conform to a style decision not to capitalise forms of the verb ‘to be’, a feature of Intelligent Editing’s Smart Capitals style.

I don’t know about you, but I’m getting a headache.

What else now?

Stuck in the middle, according to Hart’s at least, are pronouns and adverbs, the may or may nots of a title. So, just a reminder of what they are:

- Pronouns are stand-in words and phrases for a name or names, from they to Her Majesty (which is actually capitalised for quite another reason, but you get the idea). Some are short enough to seem unimportant: he, it, but in general they are capitalised.

- Adverbs answer questions such as ‘how?’ ‘when?’ and ‘where?’. They modify verbs, adjectives, prepositions, determiners, other adverbs, and sometimes whole clauses and sentences. Examples are happily, then and quite. Adverbs generally have at least four letters but the two-letter as can also be an adverb, as in ‘title case is different from sentence case, and just as annoying’.

Why might we not capitalise these words? One reason might be aesthetics. We’ll consider this in a minute, but first let’s look at colons and hyphens.

Capitalising after colons and hyphens

Say you’re applying maximal capitalisation style to a title and there’s a colon, and after it is an article. What do you do then? In many styles you’d capitalise whatever word follows a colon, even if it’s a word that you wouldn’t usually capitalise:

Title Case: A Miserable Exploration

So there’s one more complication for you. Sorry.

How should we treat text after a hyphen? Many of us are used to seeing that lowercase e after the hyphen in the title of Butcher’s Copy-editing (last published in 2006), and reflecting that it must be like that for a reason and therefore maybe we’d better do the same, although some of us have closed up the hyphen in ‘copy-editing’ in our own communications (because of this exact issue? Er, maybe) so we don’t have to make this decision any longer. However, it’s worth remembering that even though Butcher’s is a titan in its field, it’s still produced within a house style, and house style should always be your first port of call for such decisions. But if it doesn’t cover this point? Hart’s says:

When a title or heading is given initial capitals, a decision needs to be made as to how to treat hyphenated compounds. The traditional rule is to capitalize only the first element unless the second element is a proper noun or other word that would normally be capitalized … In many modern styles, however, both elements are capitalized.

You could imagine this working with ‘Copy-Editing’, as both parts of this compound can stand alone as words, but what about when there’s a prefix before the hyphen, such as ‘Re-’, ‘Ex-’ and ‘Co-’? In a recent discussion on the CIEP forums Sue Littleford gave an alternative to modern-style capping: ‘The guidance I usually follow … is to cap the second part if the first part can stand alone, and if not, not.’

The final judgement

Say we’ve capitalised our nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns and adverbs, and lowercased our articles, conjunctions and prepositions, and we’ve made any necessary exceptions according to our style guide. What’s the final arbiter for decision making about capitals? In the end, both Hart’s and Dreyer defer to how things look. Dreyer talks of the ‘visual euphony’ that might influence a decision to capitalise (or not), and this is what Hart’s says:

Exactly which words should be capitalized in a particular title is a matter for individual judgement, which may take account of the sense, emphasis, structure, and length of the title. Thus a short title may look best with capitals on words that might be left lower case in a longer title.

To retain some semblance of consistency, review your titles against each other in a list, which you can do in Word (left-hand navigation pane) or simply by copying and pasting them into a separate document and studying them hard. Then try your best to articulate the basis of your decisions on the style sheet for those who follow you in the process. Doing this will help you, too.

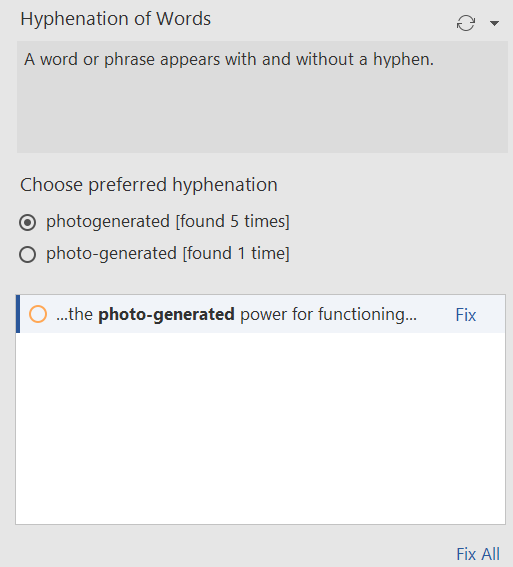

If you’re working in a US style, a miraculous link was posted on the CIEP forums a few weeks ago that can act a good basic guide to capitalising in title case (particularly after hyphenation), though, like everything to do with title case it seems, it shouldn’t be seen as absolutely conclusive. But that might be a good thing. In an increasingly automated arena, assessing the nuances of capitalisation could be one of the final areas that will stay firmly within the realm of editorial judgement.

Resources

CMOS Shop Talk. ‘Is “Is” Always Capitalized in Titles?’, https://cmosshoptalk.com/2021/08/24/is-is-always-capitalized-in-titles/

Benjamin Dreyer (2019), Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style. Penguin Random House UK, pp. 248–51.

Amy Einsohn and Marilyn Schwartz (2019), The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A guide for book publishing and corporate communications. University of California Press, pp. 185–7.

Intelligent Editing, ‘Capitalization of Headings’, https://intelligentediting.com/docs/perfect-it/understanding-perfect-its-checks/capitalization-of-headings.html

New Hart’s Rules (2014). Oxford University Press; section 8.2.3

About Cathy Tingle

Cathy Tingle holds the variously capitalised titles of CIEP Advanced Professional Member, copyeditor, proofreader, tutor and CIEP information team member.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: bookshelf 1 by Karim Ghantous on Unsplash, bookshelf 2 by Jonathan Borba on Pexels.

Posted by Harriet Power, CIEP information commissioning editor.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.

In January we launched the

In January we launched the

1. Tech talk

1. Tech talk 4. Lost words

4. Lost words Rosie Tate is co-founder of

Rosie Tate is co-founder of