In this post, Hazel Bird takes a look at the documentation that can help freelance proofreaders and editors to keep on top of the business side of things – from scheduling and accounting to thinking about CPD and business strategy.

Your style sheets are slicker than a greased exclamation mark and your handover notes template is perfectly balanced between conciseness and comprehensiveness. Your macros are practically doing the editing for you (well, not quite …) and you have shortcuts set up with author queries to handle just about anything a client can throw at you.

In other words, you’ve got this editing thing down pretty well. But what about your wider business? What strategic and administrative documentation have you set up and how well is it working for you? Does it enable you to understand what’s going on in your business now, what happened in the past and how to achieve your future goals?

This post looks at some of the core non-editorial documentation you might want to consider setting up. The list is based on the lessons I’ve learned over 13 years as a full-time freelancer – simply put, this is a list of the documentation I wish I’d established and used from the get-go.

It’s important to note from the start that these ‘documents’ don’t necessarily have to be separate – it’s perfectly OK to address two, three or more of the functions below in a single document if that’s what works best for you.

1 Scheduling and workload

Let’s start with the absolute basics. You’ll need somewhere to write down all the work you have booked in, any prospective work beyond that, and all the key dates. You might also want to estimate how many hours each block of work will take you. From this basic information, you can then plan long term (so you know when you’re free for additional work) and short term (so you can see in detail how you’ll meet your immediate commitments).

There are endless options for scheduling, from a humble spreadsheet (such as Google Sheets) to project management software (such as Trello) to business management tools (such as 17hats). I record my schedules and key tasks in a database and then pull the information out into a spreadsheet that shows me week by week, in a highly visual way, how much work I have booked in over the next year (long-term planning). I also use this data to draw up a handwritten plan every two weeks showing exactly when I will complete what I’ve got coming up (short-term planning).

This is a simplified mock-up of one of my two-week plans. On the left is a list of all the projects that will have some sort of activity over the next two weeks. Brackets signal projects that are in the background and very unlikely to require active work; ticks mean I have inputted all work for the project into the grid on the right. In the grid, the circled numbers are days of the week and an exclamation mark means I have holiday or some other potentially disrupting commitment on that day. Non-paid work and general admin are not scheduled as my project scheduling deliberately leaves time free for those tasks over the course of the week. I do, however, note down specific events, such as the client calls and webinar. ‘X’ is an important one – it means ‘answer emails and do any other bits and pieces that need to be done today’. As I complete projects and work, I cross them off (the cross-outs in this mock-up are as if I were halfway through day 2 of week 1).

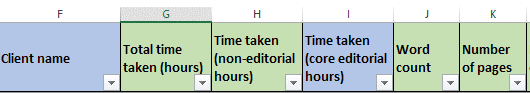

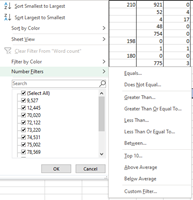

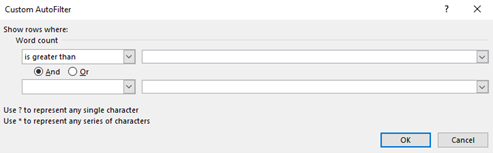

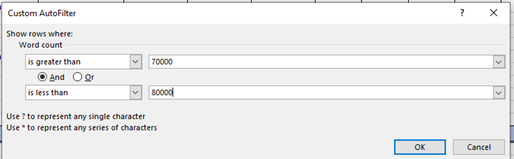

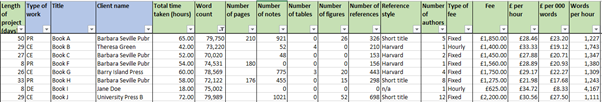

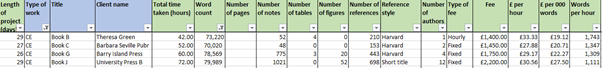

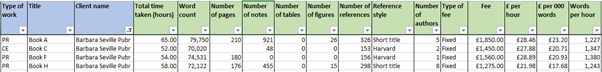

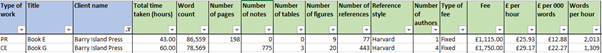

2 Word counts, fees and time

This is where you get into the nitty-gritty of your day-to-day work. How quickly can you edit? Does it vary by client, type of work or subject matter? Are you happy that the amount you’re being paid fairly compensates you for the amount of work you’re putting in? Can you make a reasonable estimate of how long a potential project might take?

Recording word counts, fees and the time you take will enable you to answer these questions and many more. The answers will feed into your reporting (see below) and also help you to control your workload (and hence take care of your mental wellbeing).

Whatever system you choose for your scheduling will likely have the ability to record these details, or you might want to set up a specific spreadsheet for this purpose (or, if you’re a CIEP member, you can use the Going Solo toolkit ‘work record’ spreadsheet). For time tracking, some people use tools such as Toggl, which can integrate with other software.

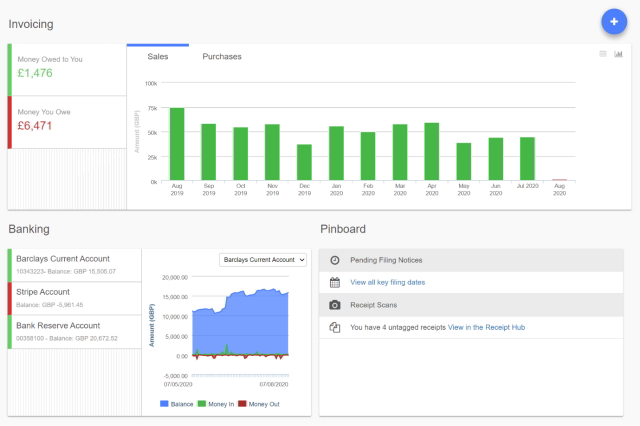

3 Finances

You’ll need some sort of way of tracking invoices raised, whether they’ve been paid and any expenses. Obviously this should be in a format that enables you to meet the tax reporting requirements in your region. Beyond that, the level of detail and the format are up to you. You might find specialist software helpful, but a spreadsheet (perhaps with some conditional formatting to flag when an invoice is overdue) can be more than enough. You might even just add a couple more columns to your scheduling spreadsheet to record when a project has been invoiced and paid. If you’re a CIEP member in the UK, you could try the Going Solo toolkit ‘accounts’ spreadsheet.

A hard-earned tip is to actively track your cashflow too. By this I mean forecasting when you expect future payments to arrive (for all upcoming projects – not just the ones you’ve already invoiced) and your anticipated expenses (including the ‘salary’ you pay yourself). Although this can take a bit of time, it can really help your mental wellbeing as it avoids surprises. Susie Jackson has a lot of great tips on clear financial thinking for freelancers.

4 Leads, enquiries and quotes

This is all about tracking who’s contacted you and why, the outcomes, the status of any ongoing discussions (eg if you’ve sent out a quote and are waiting for feedback) and the details of any organisations you’re interested in approaching in the future.

The scale and format of this document will vary hugely from freelancer to freelancer, depending on the nature of their business and what they’re trying to achieve. You might want a complex CRM-type system that enables easy day-to-day tracking and communication with clients, or a simple spreadsheet might equally serve you very well. Just make sure your chosen tool has the capacity to record everything you’ll want to report on (see ‘Strategy and reporting’ below).

5 Marketing

I’m very much not a marketing expert, so I like to keep this as simple as possible. However, if this is an activity that you enjoy or that is particularly important to you at the moment (eg if you’re pivoting your business in a new direction), you might want to give this more space within your business. Louise Harnby’s posts are a perennial favourite in the editing community on the topic of marketing.

My major marketing activities are my website, my blog and my CIEP directory entry. For my website and directory entry, I keep an ongoing list of tweaks plus, if I’m building up to a major update, a more substantial document where I rewrite my content. For my blog, I used to have a separate spreadsheet but I now track my posts in WordPress’s native interface, which I’ve found has saved a huge amount of time.

All of my marketing activities are heavily influenced by my strategy document (see below).

6 Log of positive feedback and lessons learned

As advocated by Erin Brenner and many others, the ‘win jar’ is a hugely important morale booster, especially for freelancers who spend much of their time working in isolation. Whether you choose an actual jar, yet another spreadsheet or an A1-size poster of your greatest hits to hang on the wall, it’s wise to remind yourself of all the positive comments you’ve received. After all, if you don’t keep in mind what your clients appreciate, it’s harder to deliver on their needs.

At the same time, though, a modest log of lessons learned can be a really valuable tool. I always make sure to briefly write down when something doesn’t go to plan – for example, if I take on a project with red flags and then regret it, or if it turns out partway through a process that a client wasn’t fully clear on some aspect of my service. I then make sure to plug the gaps by taking action to avoid the same thing happening in the future – for example, by updating my checklist of ‘things to consider’ when evaluating a potential new project or by updating my quote package so future clients hopefully won’t experience the same misunderstanding in the future.

7 CPD log and planning

It can be helpful to keep a list of the continuing professional development (CPD) activities you’d like to do. Otherwise it can be easy for months or even years to slip by in which you’ve completed an awful lot of projects but not furthered (or even maintained) your skillset at all. It can be particularly helpful to use this document to plan the time and financing needed for any ‘big’ courses, such as learning a brand new skill. But it’s also good to jot down books, podcasts, websites and the like that you can use to help you keep up to date with whatever developments are relevant to your field. Again, CIEP members could use the Going Solo toolkit ‘training and CPD’ spreadsheet for this.

8 Terms and conditions

If you’re working with non-publisher clients then you’ll probably want a document you can share with them that lets them know the legal and practical implications of doing business with you. I think of my T&Cs as a document that evolves with my business and I update it at least annually.

9 Strategy and reporting

Not everyone starts their business with a fancy formal business plan. But at some point you’ll probably find it helpful to write down all those ‘what ifs’ and ‘maybe I coulds’ and ‘I think I’d like tos’ in a single place to keep track of them. The purpose of this document is to set out what you want your business to do for you and how you plan to achieve that.

Your goals can be as grand or as simple as you like. For example, you might want to write a detailed financial and marketing plan to help you completely change your client base over the next three years. Or you might prefer to keep things roughly as they are but achieve a modest hourly rate increase each year.

Where this becomes really powerful is when you pair it with reporting on how your business has performed in the past. I’ve written about how and why I write an annual report for my business here and here. Once you understand your past performance, you’re better able to set realistic future goals and make wiser decisions about what you want your business to achieve for you.

I do my strategy and reporting in Google Docs and use this information to populate to-do lists in Trello with the actions I’ve chosen to keep me on track. Your reporting data will come from all the sources above – you’ll just be viewing it in the rear-view mirror.

In choosing how to address each of the areas above, keep in mind that your documentation should be flexible, manageable and focused on outcomes rather than tracking for its own sake. It should also be capable of evolving – after all, who knows what you will want your business to be doing in five, ten or even twenty years’ time?

Resources

The Going Solo toolkit, which is free to all CIEP members, includes a collection of Excel spreadsheets that are set up to record most of the information covered in this post.

The Editor’s Affairs (TEA) is another series of Excel spreadsheets designed specifically for editors to keep track of their business data.

The short book The Paper It’s Written On: Defining your relationship with an editing client, by Karin Cather and Dick Margulis, is helpful for crafting your own T&Cs.

About Hazel Bird

Hazel Bird is a freelance editor and editorial project manager who works with businesses, charities, public sector organisations, publishers and authors around the world to deliver some of their most prestigious publications. She tries to see the detail and the big picture all at once – the wood and the trees – and has learned over the years how important good documentation is in achieving that!

Hazel Bird is a freelance editor and editorial project manager who works with businesses, charities, public sector organisations, publishers and authors around the world to deliver some of their most prestigious publications. She tries to see the detail and the big picture all at once – the wood and the trees – and has learned over the years how important good documentation is in achieving that!

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: notebook by Jessica Lewis Creative on Pexels, two-week plan by Hazel Bird, laptop and notebook by Ketut Subiyanto on Pexels.

Posted by Harriet Power, CIEP information commissioning editor.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.