In this blog post, three experienced editors explain what they do in between receiving a manuscript and properly getting stuck into editing the text. From running macros and styling headings, to checking references and making sure the brief is clear, tackling certain jobs before starting to edit the text can improve and speed up the whole editing process.

Hazel Bird

For me, the stage between receiving a manuscript and properly starting to copyedit the text is about two things: (1) ensuring I have a solid understanding of what the client needs me to do and (2) proactively identifying any problems within the manuscript so I can get started on fixing them straight away.

So, for step 1, I’ll do things like:

- checking the manuscript matches what I was told to expect in terms of word count and components

- checking I have all the necessary briefing materials and instructions from the client

- checking I understand the context in which the project will be used (eg for an educational project, the level of qualification, the ability range of the students, where they will be geographically and any other resources they might use alongside this one)

- reminding myself of the details of the agreed level of service and any special aspects of the work

- getting in touch with whoever will be answering queries on the text (if they aren’t the client) to introduce myself and agree how the query process will be handled.

If there are any discrepancies, ambiguities or stumbling blocks, I’ll write back to the client straight away to open a discussion.

For step 2, I’ll start digging into the actual text but on a holistic, overarching basis. I have a load of macros that I run to clean up the formatting and highlight things I’ll need to check or fix later, during the in-depth edit. I’ll then style the text’s major headings so that they appear in the Navigation Pane in Word (I find this bird’s-eye view of the manuscript essential as it speeds me up and helps me to identify big-picture issues). At the same time, I’ll examine the structure and check it fits with any template or scheme I’ve been given by the client. Next I’ll run PerfectIt to fix some more style basics and begin to compile a style sheet with what I’ve found.

My final task within step 2 is to edit the references. A lot of my work is with clients whose authors don’t handle referencing every day, so I frequently find issues with reference completeness or even technical issues with the entire referencing system. Identifying such issues early on means there is time for everyone involved to discuss how to proceed in a relaxed manner, without time pressure. And, from an editing point of view, I find editing the main text goes so much more smoothly when I know the references are already spick and span.

The result of all of the above tasks is that once I get started on the main text, I should have minimised the number of surprises I’ll find and thus maximised the chance of the project being completed without hiccups and on time. I will also have fixed or flagged (to myself) as many routine, repetitive tasks as possible so that when I get into the actual line-by-line editing, I can devote the majority of my attention to flow, clarity, accuracy and whatever else the client wants me to refine – in other words, the parts of the editing where I can really add value.

Hester Higton

Exactly how I start work on a manuscript depends on the length: I’ll do things differently for a journal article and a lengthy book. But my rule for any project is to make sure that I’m batch-processing, so that I use my time as efficiently as possible.

If I’m working on an article for one of my regular journals, I’ll start by making sure that the file is saved using the correct template. Sometimes this will be one supplied by the client; if they don’t have a preferred one, I’ll use one of my own that eliminates all extraneous styles.

Then I’ll run FRedit. I have customised FRedit lists for all my repeat clients. These not only deal with the standard clean-up routines but also adapt the document to the preferred house style. I use different highlight colours to indicate aspects I want to check (such as unwanted changes in quotations) and I’ll run quickly through the document to pick these up. As I’m doing that, I’ll make sure that headings, displayed quotations and the like have the correct Word styles applied to them.

Next on my list is PerfectIt, which allows me to iron out remaining inconsistencies in the text. I use a Mac so I can’t customise my own style sheets, but the new Chicago style option has made my life a great deal easier!

After that, if the article uses author–date referencing I’ll cross-check citations and references, flagging missing entries in each direction. I’ll style the references list and either note missing information for the author or check it myself if I can do so quickly. If all the references are in notes, I will run a similar style check, editing the notes themselves at the same time.

Finally, I’ll look at the formatting of any tables and figure captions to make sure that they match the house style. I may well edit the captions at this point, but leave table content until I reach the relevant point in the text.

If I’m working on a book-length project that doesn’t have a fully defined style, I’ll start by running PerfectIt. That allows me to make decisions about spellings, capitalisation and hyphenation, all of which I note down on a word list which I’ll return to the client with the completed project. That’s followed by a more basic clean-up FRedit check. I’ll also format figure captions and tables throughout the book at this point. And if there’s a whole-book bibliography, I’ll check that and style it. But I’ll handle the notes separately for each chapter because it allows me to keep a sense of the subject matter in them when I’m working on the main text.

Katherine Kirk

The pre-editing stage is actually one of my favourite steps in the process, and I usually pair it with some great music to see me through. My whole pre-flight process takes about two to three hours, depending on the formatting and size of the document. I work mainly with novels from indie authors and small publishers, so I don’t have to worry too much about any references or missing figures and tables. Some publishers have their own template they want me to apply or some specific steps that they like me to take, but here’s what I do for most indie novels that come across my desk.

I start by reviewing our agreement and any extra notes the author has passed along, and I add them to the style sheet. I use a Word template for my style sheet that has all the options as dropdowns, and that saves loads of time.

The next thing I want to deal with is any bloat or formatting issues; these might affect how well the macros and PerfectIt run. I attach a Word template that has some basic styles for things like chapter titles, full-out first paragraphs, and scene breaks, as well as a font style for italics that shades the background a different colour (great for catching italic en rules!). Styling the chapter titles and scene breaks first makes it easy to find the first paragraphs, and check chapter numbering. Then I skim through for any other special things needing styling. I can set whatever is left (which should just be body text) in the correct style. The aesthetics of this template don’t really matter to the client; I use a typeface that is easy for me to read and makes errors like 1 vs l more obvious. I can revert all the typefaces to a basic Times New Roman at the end. I save this as ‘Working Copy – Styled’ just in case the next step goes horribly wrong …

Now that I’ve cleared up the clutter, I ‘Maggie’ the file (select all the text, then unselect the final pilcrow, and copy and paste it into a new document) to remove the extra unnecessary data Word has stored there. It can drastically reduce the file size and helps prevent Word weirdness like sudden jumps around the page or lines duplicating on the screen. If you’ve styled all the elements of the text properly beforehand, you shouldn’t lose any formatting, but be careful! That’s also why I do this as early as possible, rather than risk losing hours of work. I save this file as ‘Working Copy – Maggied’ so I can see if the file size has decreased, and if it’s all working smoothly, this becomes my working file.

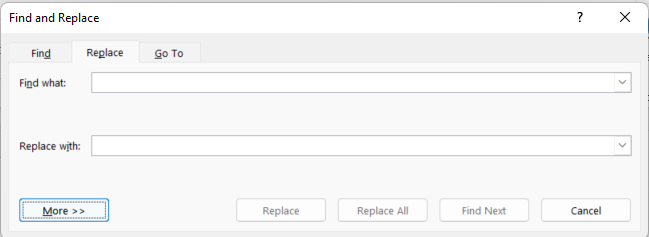

I have a checklist of silent changes that I include in the style sheet. I usually start by doing some global replacements of things like two spaces to one, a hard return and tab to a paragraph break (^l^t to ^p), and two paragraph breaks to one (and repeat until all the extras are gone). Some authors like to make their Word documents look like the final book, and they might use extra paragraph breaks to start a chapter halfway down the page. This can cause problems later when the reader’s screen or printer’s paper size is different to what the author had, so it’s got to go!

I run analysis macros like ProperNounAlyse to catch misspelled character names, and I add them to the style sheet. I might also run HyphenAlyse and deal with any inconsistent hyphens in one big swoop. Then I run PerfectIt and work through it carefully, making note of decisions on my style sheet. I review any comments that might have been left in the text by the author, publisher or previous editors, mark them with a query if they still need to be dealt with, and remove the rest.

Finally, all systems are ready to go, and I launch into the main pass.

Resources

Sign up for the CIEP’s Efficient Editing course to learn more about how to approach an edit methodically and efficiently.

Check out the blog posts Making friends with macros and Two editors introduce their favourite macros to learn how to use macros before (or during) an edit.

About Hazel Bird

Hazel Bird runs a bespoke editorial service that sees the big-picture issues while pinpointing every little detail. She works with third sector and public sector organisations, publishers, businesses and non-fiction authors to deliver some of their most prestigious publications.

Hazel Bird runs a bespoke editorial service that sees the big-picture issues while pinpointing every little detail. She works with third sector and public sector organisations, publishers, businesses and non-fiction authors to deliver some of their most prestigious publications.

About Hester Higton

Hester Higton has been editing academic texts for publishers and authors since 2005. She’s also a tutor for the CIEP and currently its training director.

About Katherine Kirk

Katherine Kirk is a fiction editor who has lived all over the world, including China, South Korea, Ecuador, and Morocco, and she’s not done yet. She works on all types of fiction for adults, especially Science Fiction, Fantasy and Literary Fiction. She is a Professional Member of the CIEP.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: brick wall by Tim Mossholder, glasses on keyboard by Sly, coffee by Engin Akyurt, all on Pixabay.

Posted by Harriet Power, CIEP information commissioning editor.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP