A key part of any training and CPD we undertake is taking notes that we can look back on for reference. But which is best: good old pen and paper, or modern apps? Andy Coulson contrasts and compares.

I am an unashamed paper note-taker. There is something about using paper and a pen or pencil that just feels better. I think the physical action of writing is a part of it: research in education and psychology suggests there is a link between handwriting and memory formation. There is certainly research around the cognitive benefits of handwritten note-taking (for example, Mueller and Oppenheimer’s ‘The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking’). I’ve tried various digital solutions and they just don’t quite cut it for me, but they might be preferred by some.

Why make notes?

Note-taking is a key study skill students use to record key information about a topic and create something they can then review and learn from. Many university websites offer good note-taking guides, for example the University of Reading and the Open University. Cornell University goes a step further and has its own note-taking system, summarised here.

All these have a few things in common: notes are short-form text, summarising key points to act as reminders; they should ask or stimulate questions about the topic; and they should allow the student to accurately review the material later.

Paper notes: The pros and cons

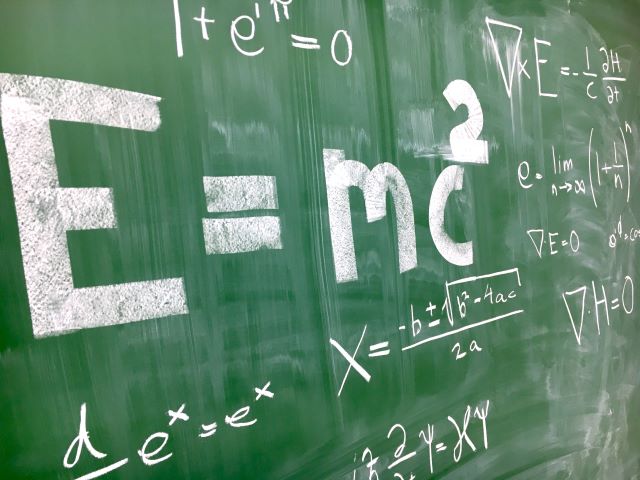

I think one of the things that I like about paper notes is that they don’t have to have a fixed structure: if they capture the key information in a way that allows you to understand and recall it, then they work. Handwritten notes can include marking up or annotating printouts (for example, with a highlighter or marginal notes); creating a structured outline using nested bullets, diagrams, tables and graphs, and mind maps or spider diagrams; or mostly graphical approaches like Sketchnotes. If you are anything like me, your notes end up with a mix of different things – sometimes a doodle or sketch catches an idea, and sometimes words are enough.

While handwritten notes have an advantage in helping us to understand and remember what we are learning, organising them can be more difficult. The more formal and structured systems, such as Cornell’s, encourage you to review and rewrite notes to help understand and retain the information. Using paper this is a slow job, but again it is all helping the information sink into your brain – it is a part of the learning process. By contrast, we have got used to storing everything and quickly searching for it with reasonable accuracy in the digital world. So, do the digital alternatives offer us a real advantage by managing the organisation?

The digital app alternatives

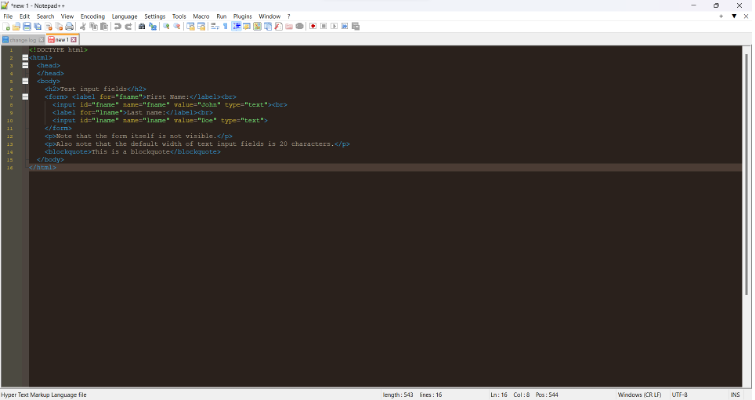

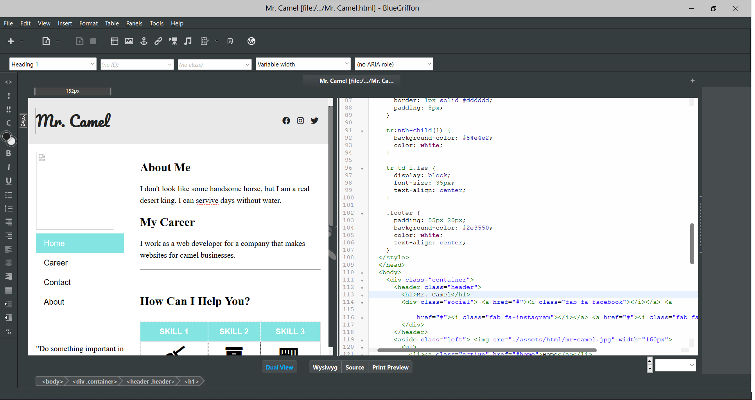

Three popular digital note-taking apps are Microsoft’s OneNote, Google Keep and Evernote. The first two are freely available with a Windows, Office or a Google account. Evernote has a feature-limited free version, and paid versions with varying degrees of sophistication. All three of them also have mobile apps that link to the desktop or web app, allowing you to sync your notes across devices. I’ve used both Evernote and OneNote and they are both very comprehensive programs. They do slightly different jobs, but there is a big crossover in the middle.

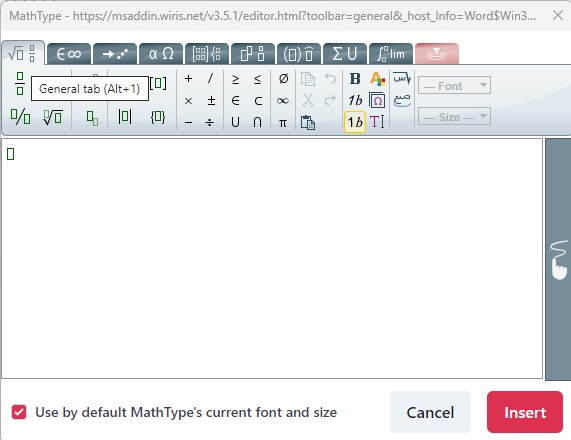

Evernote is particularly good at grabbing content from sources such as web pages and, with a paid plan, you can add markup to these. Information is organised as pages, referred to as ‘notes’, that can be grouped in notebooks and linked. When you create notes there are a lot of templates you can use, including a Cornell Notes-specific one. In a note, you can add text or images, and a wide variety of other material. The editing screen is quite similar to Word or Google Docs, with material added in a linear up/down fashion as you would in Word. There are also features to create checklists and a link to Google Calendar, allowing Evernote to work as a capable task manager as well as a note manager.

OneNote supports most of the same features as Evernote. One big difference is the much more freeform way that you can add things to a note (or ‘section’ in OneNote terminology) where blocks of text or images are not fixed in a linear flow like they are in Word. For example, when you add text to a page, say a paragraph or bullet list, you add it as a box. These boxes can be moved around on the page in relation to each other, making the structure of your notes very easy to reorganise. There are a lot of quick formatting options that help you to highlight and flag elements in the text, such as ‘tickable’ to-do list bullets, highlighted styles for definitions or things to remember for later, and icons for phone numbers or email addresses.

By contrast, Google Keep is a much simpler app and to my mind is more like a digital block of sticky notes. You create text notes with a more limited range of features, including embedding images. The clever bit is that you can add labels like those Gmail uses, to group and organise those notes.

I think OneNote gets closest to the flexibility of handwritten notes, and I can imagine that with a tablet and stylus it gets even closer. However, I don’t think any of these quite replace the functionality and convenience of a pad and pen; for me, at least.

As I mentioned earlier, part of the learning process is to review and perhaps rewrite your notes. Perhaps a hybrid option is to treat that rewrite as a good point to digitise your notes, particularly if you want them to be digitally searchable in future.

A reMarkable solution?

There is one more technical solution that might offer the best of both worlds. The reMarkable tablet aims to provide a paper-like experience on a digital tablet. It incorporates handwriting recognition so handwritten text can be converted to computer text, allowing it to be searched. The reMarkable system uses a folder system, just like your PC or Mac, and can sync documents with popular file storage services like Google Drive. There is also a desktop program that allows you to access and organise all your notes on your PC or Mac. The downside is of course the cost (around £300), but it is comparable to a mid-range phone or tablet, and this could be a really useful tool for many people.

About Andy Coulson

Andy Coulson is a reformed engineer and primary teacher, and a Professional Member of the CIEP. He is a copyeditor and proofreader specialising in STEM subjects and odd formats like LaTeX.

Andy Coulson is a reformed engineer and primary teacher, and a Professional Member of the CIEP. He is a copyeditor and proofreader specialising in STEM subjects and odd formats like LaTeX.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: header image by Kelly Sikkema, handwriting by Eleni Koureas, computer keyboard by Sergi Kabrera on Unsplash.

Posted by Belinda Hodder, blog assistant.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.