If the past few weeks have been something of a blur, let us assist you by at least reminding you of all the great new editing and publishing content the CIEP shared in April and May. Thanks to all the contributors, and also to everyone who liked, commented, clicked on a link or shared our content. That support is hugely important, and we appreciate you!

References

One of the themes in our new blog content for April and May was the much-dreaded task of editing references.

Checking and styling references is a time-consuming job that requires a great deal of focus. Sue Littleford writes, ‘When I’m copyediting, the references can take longer than the main text.’ In our Flying Solo series, Sue provides us with welcome time-saving solutions in how to edit references more efficiently (and more profitably).

Thankfully, there are tools at our disposal to make editing references less excruciating. In our Talking tech series, Andy Coulson looks at how Find and Replace and using wildcards can speed up editing and styling references.

For editors and proofreaders, the CIEP forums are a great place to share tips, and seek advice, on all aspects of editing. Our forum moderators searched the threads for our members’ experiences and came up with a round-up of invaluable referencing tips.

References may be something that you don’t have to deal with very often in your area of editing; however, a basic understanding of each of the referencing systems is essential for a well-rounded knowledge of the job. The CIEP’s training director, Jane Moody, looks at how editors and proofreaders can become pros at dealing with references.

The CIEP’s comprehensive course on References is ideal for those wanting to improve their knowledge of the subject.

And for those who want a taster of what you should know about References, our fact sheet is available free for CIEP members. (This link will only work if you’re logged in to the CIEP members’ area.)

Subjects and specialisms

If you speak to a dozen editors you’ll probably find that workloads, workflow and tasks will vary from individual to individual. In addition, some of us are subject experts or genre specialists working with publications that benefit from specific background knowledge and/or experience. In April and May, we posted content that showcased specialisms.

In a popular blog post, four CIEP members discuss their particular areas of expertise – cookbooks, school textbooks, RPGs (role-playing games) and construction – to give a flavour of some editorial niches that may be new to you.

Lisa Davis is a children’s editor and points out that children’s books tend to get, mistakenly, lumped together as one genre. She discusses age appropriateness in children’s literature, how to tell whether content is suitable for specific age ranges, and considers the importance of who is reading the book and how it gets into their hands.

A popular post was Harriet Power’s insight into how she became a development editor and what her freelance working week looks like. Development editing is a term that can prove a bit mysterious even among editors!

Catherine Booth’s excellent article on medical editing sparked some debate on whether a medical background is essential for becoming a medical editor. It’s evident that there are many editors editing outside of their subject expertise, using transferable skills in publications where their training maybe comes from experience rather than formal study. Our pathways to work as editors are certainly fascinating!

The CIEP and CPD

Early May was the deadline for CIEP membership renewal. To remind members of what the CIEP has to offer, five editors discuss what they gain from being a member of the CIEP, and why they renewed their membership for another year.

Local group meetings are an enriching aspect of being part of the CIEP. Carla DeSantis discussed the advice presented by Malini Devadas at a recent Toronto CIEP local group meeting on how freelance editors can earn more money.

We heard from a new CIEP member, too. Taylor McConnell, a new freelance editor whose specialist area is social sciences, describes how he got into proofreading and editing, and what his weeks typically look like.

The London Book Fair returned this spring as an in-person event. Two CIEP members, Aimee Hill and Andrew Hodges, attended for the first time and recorded their thoughts and experiences. Should you bother with all the seminars? Is it worth handing out business cards? And isn’t it all a bit overwhelming? They give their tips, advice and first impressions.

Resources we promoted in April and May

Web and digital content

Whether you are a potential client looking for a web editor or an editor looking to diversify. the CIEP has resources.

We have an online course on Web Editing which will give you the skills to help you to work efficiently and harmoniously with website designers.

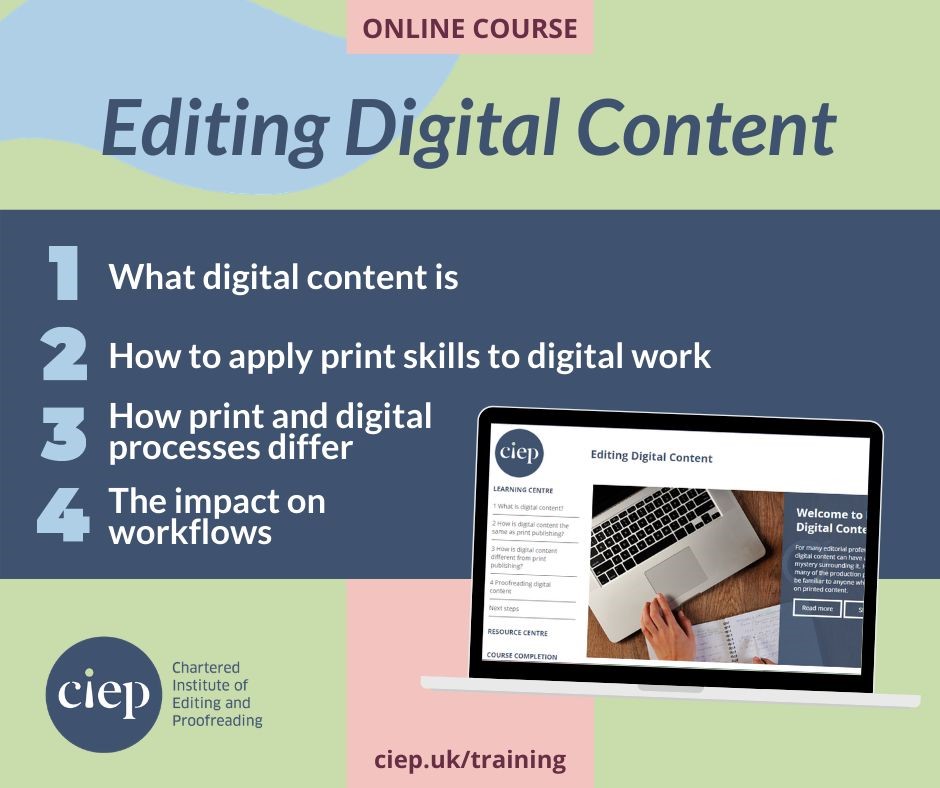

The CIEP Editing Digital Content course is ideal for editors who want to expand their capabilities and understanding into content that is not published in printed form. The course explains the key differences between print and digital media.

Looking for a professional web-content editor? The CIEP’s Directory of Editorial Services lists members with proven qualifications, substantial experience and good client references.

Medical editing

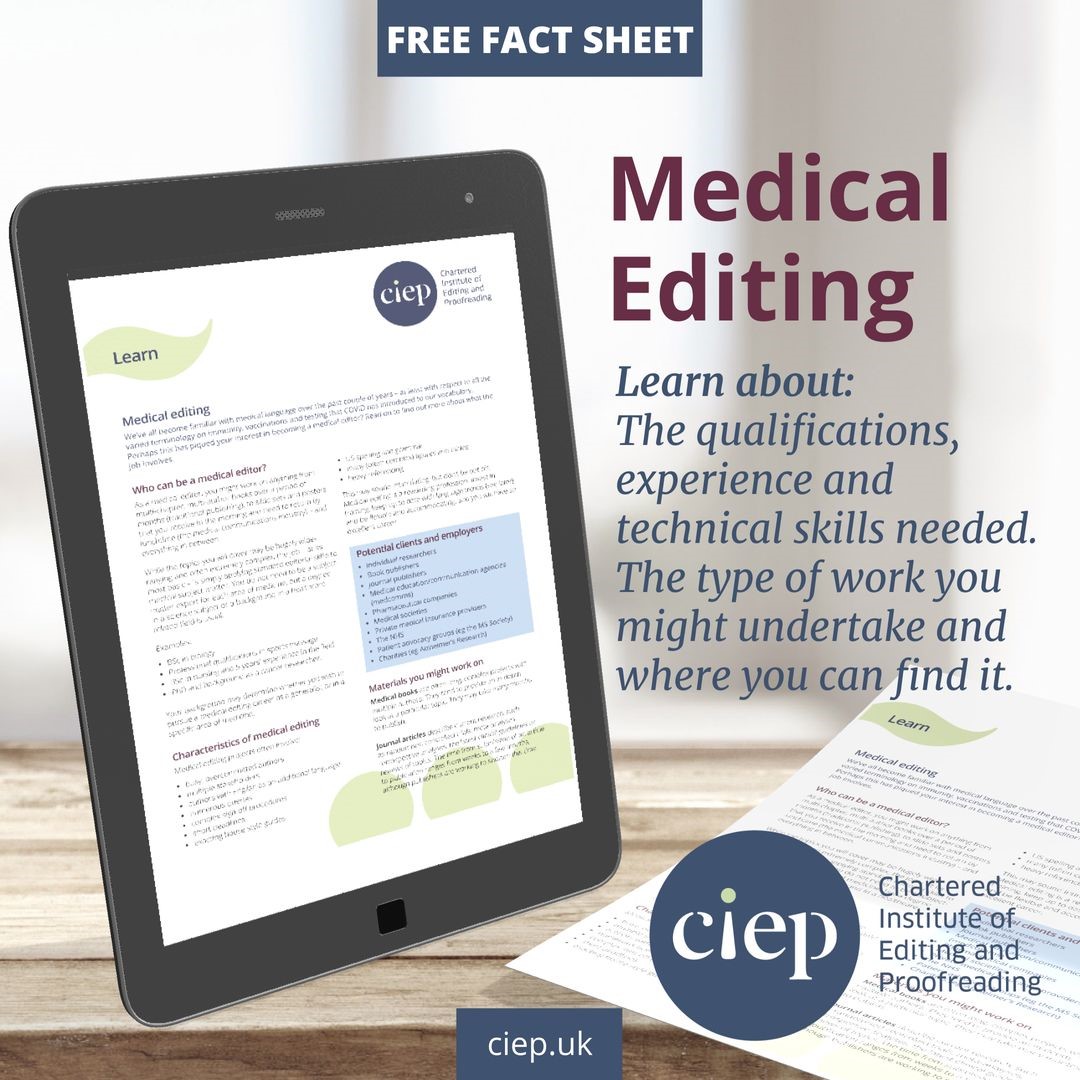

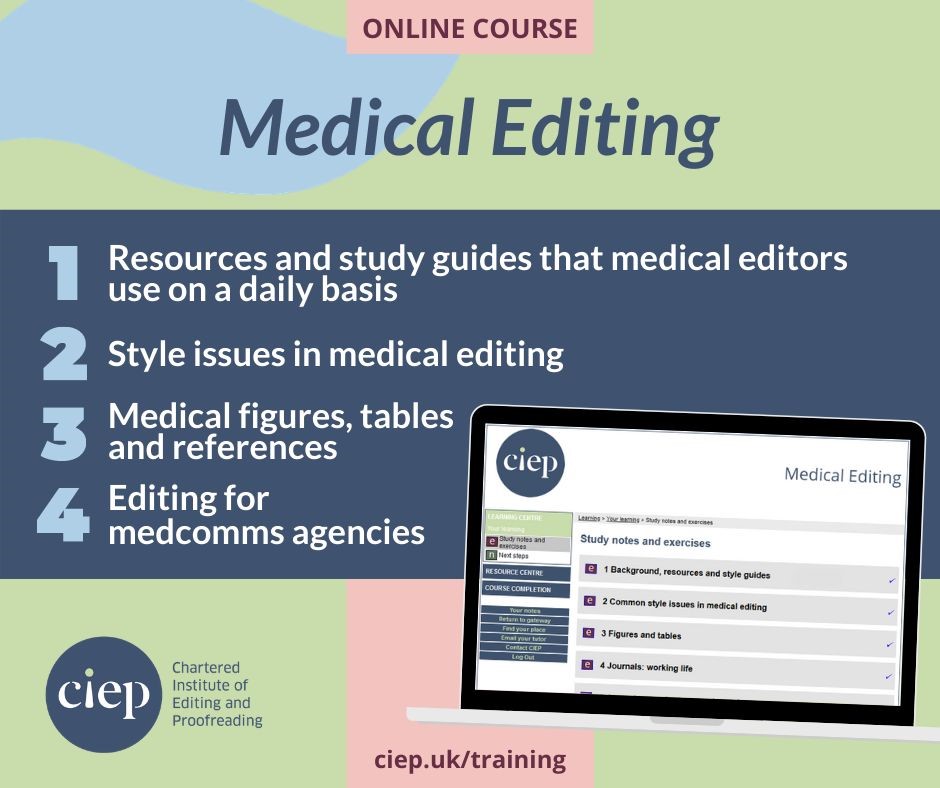

We promoted two recent additions to our content on medical editing – a fact sheet and a guide to Editing Scientific and Medical Research Articles, which are free for CIEP members.

Why not check these out and consider whether our course on Medical Editing is of interest?

Conference

Don’t miss out! Have you booked yet?!

The 2022 CIEP conference will be held at Kents Hill Park, Milton Keynes, and online, from 10–12 September 2022. Join us this September! There will be plenty of opportunities to network and socialise, in person and online.

The deadline for booking an in-person conference place is 5pm on Friday 8 July; the deadline for an online place is 5pm on Friday 2 September.

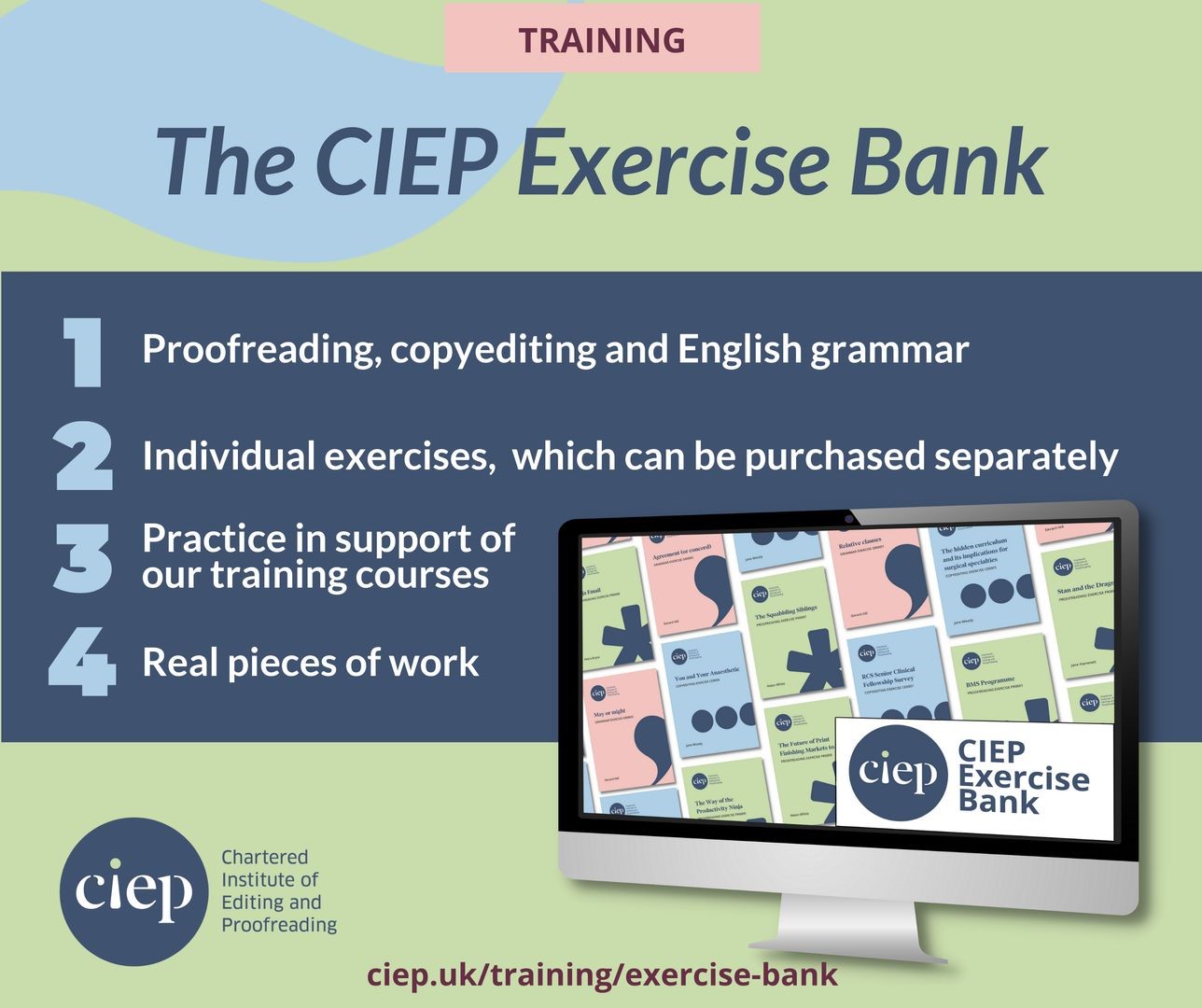

Exercise bank

We pr omoted ways to back up your learning via the Exercise Bank. It’s a collection of individual exercises – based on real pieces of work – covering proofreading, copyediting and English grammar, and providing practice in support of our core training courses. There’s a discount for CIEP members.

omoted ways to back up your learning via the Exercise Bank. It’s a collection of individual exercises – based on real pieces of work – covering proofreading, copyediting and English grammar, and providing practice in support of our core training courses. There’s a discount for CIEP members.

Quiz 14

Last – but not least – you really should test your language knowledge and pun tolerance with our fun new quiz!

Keep up with the latest CIEP content. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: grass by jplenio on Pixabay.

Posted by Harriet Power, CIEP information commissioning editor.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.