Editors may be most familiar with Microsoft Word and Adobe Acrobat but clients are increasingly publishing content on other platforms, such as Google Docs and content management systems (CMS). Hannah Sapunor-Davis demystifies some of these newer ways of working.

First, a bit of context: I don’t work on books, and I don’t work with typical publishers. I primarily work with designers, non-profits, business owners and digital publishing agencies. I find myself more often in Adobe, Google Docs, various content management systems (CMS) and product information management (PIM) systems than in Word.

So I wanted to share some insight into how working on non-Word platforms might change up your regular editing routines. I won’t go into detail about how the functionality and tools differ. There are lots of tutorials online for that, and it really depends on what platform you’re using, what updates have happened, and, maybe most importantly, how your client uses the platform.

But most of all, I’m here to tell you that stepping outside of the Word bubble is nothing to fear.

Real-time collaboration

Real-time collaboration is great when you need to put two heads together on a project. This can be especially helpful when you need to test functionality with a client, or when you are giving feedback in a live call. For some non-publishers, documenting changes and versions is not as important as the finished product. I found the real-time feature helpful when walking a client through edits to a webpage. We were able to come up with some new text and make changes together.

On the flip side, it can get messy quickly. A clear communication system is necessary to mitigate confusion about who should be doing what and when. In a CMS, this might be in the form of changing a status field from ‘Editing in progress’ to ‘Editing complete’, for example. For other platforms, like Google Docs, this might be communicated through an email or Slack message to the client to signal I have finished my review.

Working in the cloud

The obvious upside of working in the cloud is that you can work from most locations and most devices, as long as you have a stable WiFi connection. In the past, this has meant that I did not have to schlep my computer along with me on a trip because I knew I had access to a computer and WiFi at my destination. Even better, working in the cloud means I avoid having to store a lot of big files locally on my computer.

The other side of that coin is that if WiFi is not working properly, it can cause a major problem in your schedule. Likewise, I’ve had several instances where the platform I was supposed to work on suddenly had unscheduled maintenance. The client has always been understanding when system disruptions like this happen, but that doesn’t necessarily help when it causes a domino effect on the timelines of other clients’ projects. And I have also had it written into project agreements that I cannot work on the material on unsecured networks, which is something to be mindful of (and also good practice in general).

Different checklists

Most editors are used to creating checklists and using them in various projects. But checklists for non-Word platforms may go beyond the stylistic choices we typically navigate. For example, when editing a CMS:

- In which order should you check all the parts when it’s not in a typical top-down, left-right order layout?

- Are there any functionalities that need to be tested, such as clicking to open fields or sliding a navigation bar to the side?

- Do you need to add any steps, such as clicking ‘Save’ periodically if the platform doesn’t save automatically?

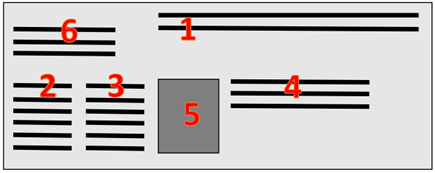

Having this order of operations clarified helps develop a rhythm for catching all the parts in design-heavy material. For example, for one retail client, I have to check marketing copy against internal product information and photos. There are a lot of different fields to review, and I have developed my own visual pathway to reviewing all the crucial spots. The order looks like this, starting with 1:

Communication with clients

Here are a few extra questions that I recommend asking your client before getting started on a project:

- Do I have all the permissions to view and edit what I need for the job? Sending screenshots or looking at your screen together with the client might help. You might not realise that a field is hidden from your view.

- Is it possible to test the functionality of the platform without making changes to the system? This could be in the form of a draft, test user account or what is sometimes called a ‘sandbox environment’.

- How will I know when I should start editing, and how will I let others know that I am done with my review? Deciding on one means of communication is key here.

- What exactly needs to be reviewed? There may be parts that don’t need to be reviewed, such as certain text fields or formatting.

- How should you save your work? The platform might save automatically or you might need to save it manually when finished.

- Do you need to document your changes? The client might not care about seeing your changes. Or maybe you need to export the copy when you’ve finished editing to have a record of your ‘version’.

- How should you send feedback? There might be a field where you can add comments and queries, or maybe you send them separately in a message.

Ready to branch out?

I didn’t follow any formal training for specific platforms. The training that I took at the CIEP and PTC covered most of what I needed to know for working with common non-Word platforms, such as Adobe and WordPress. For the rest, I learned by doing. (That’s my preferred way to learn anyway.) Each time I began using a new-to-me platform, clients understood that there was a learning curve and that certain editing functions that editors are used to, such as making global changes, might not be possible.

It doesn’t hurt to get familiar with basic HTML (HyperText Markup Language) coding. This has come in handy when I’ve noticed funky formatting, such as a word in bold that shouldn’t be or a missing paragraph break. In such cases, I can go to the HTML view and change that. And that’s one less query for the client to deal with. Of course, you should only do that if you have the permission to do so. Some clients might not want you to touch the formatting in any case. The good news is that basic HTML formatting looks very similar to the editing markup that most people learn in editing courses.

But in my experience, the skills needed for this type of work have less to do with technical know-how and more to do with a few specific soft skills. Beyond your foundational editing training and experience, you will do well if you:

- adapt to different systems easily

- learn relatively quickly

- communicate precisely.

Having worked in a variety of programs and platforms has enabled me to feel confident about approaching businesses, especially those unrelated to the publishing industry. After all, the saying goes: Everyone needs an editor. And I would like to add to that: But not everyone uses Word.

About Hannah Sapunor-Davis

Hannah is a freelance editor in Germany, originally from  Northern California. She has degrees in History/Art History and Arts Management and now loves helping individuals and small businesses write clear communication for their passionate audiences. In her free time, she likes to sew, swim, listen to podcasts or tramp through the nearby forest with her dog, Frida.

Northern California. She has degrees in History/Art History and Arts Management and now loves helping individuals and small businesses write clear communication for their passionate audiences. In her free time, she likes to sew, swim, listen to podcasts or tramp through the nearby forest with her dog, Frida.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: computer clocks by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay; bubbles by Willgard Krause from Pixabay.

Posted by Julia Sandford-Cooke, CIEP information commissioning editor.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP