In this Flying Solo column, Sue Littleford looks at how the Going Solo toolkit’s work record spreadsheet can be modified for use by fiction editors, and finds out how three fiction editors keep records about their work.

Fiction editors can’t avoid diving into non-fiction when they’re running their businesses rather than editing. The Going Solo toolkit’s work record spreadsheet (available as a member benefit – you’ll need to be logged in to the CIEP website to download it) is heavily geared towards the kind of breakdown of jobs that a non-fiction editor will find useful. Those categories don’t really work for fiction editing, beyond word count, time taken and fee charged, so I’ve been talking to three fiction editors about their own record-keeping.

Why keep records about completed work?

Editors and proofreaders in all niches need to keep track of their work and the time it takes them if they’re to have a solid basis from which to calculate quotes of cost and time. In June 2021, I looked at how to use the filter with a spreadsheet of data about the work you’ve done to get the best use of it when it comes to preparing a new quote or estimate.

Another benefit of compiling records of your work (for CIEP members and prospective members) is that you can send in a spreadsheet of the relevant details with an upgrade application instead of having to type out everything again on the application form, and it’s easy to see when you’ve achieved the necessary hours of experience.

But the main and ongoing benefit is not having to snatch figures out of the air when it comes to your pricing, and knowing the answer to the eternal question ‘How long will it take?’ You can also see if you’re getting faster or slower overall, see the impact using a new tool makes on your speeds (or a change in the material you’re working with) and, especially with repeat clients, ensure consistency in your pricing approach, and see how jobs from a particular source compare.

If you provide several services – manuscript assessment, development editing, structural editing, line editing, copyediting, proofreading – you can also see which is the most rewarding in a financial sense, which gives you best return for your time, and it helps you to tailor bundles of services at a sensible price for your business.

And now, a warning! You may be tempted to keep minimal records, perhaps just your invoices, but you really should be keeping full records: anyone planning on upgrading (and all members will need to achieve PM status to remain in the Institute, which means applying for at least one upgrade: see p4 of the Member Handbook for time limits) will need a record of the work they’ve done to show that they have the requisite hours of the right type.

In addition, in the UK, you will need to be able to show HMRC evidence of the hours you work, in order to support your calculations for tax relief on the costs of working at home. If you live (or at least pay tax) elsewhere, be sure to check your own country’s requirements – but if you still have CIEP upgrades to do, you’ll need your breakdown of hours worked available and categorised.

Facts for fiction editors is definitely A Thing!

Three editors, three approaches to record-keeping

Here’s how three editors handle their records.

1. Going Solo toolkit with modifications

Now an editor of fiction and creative non-fiction, APM Jill French started her business mainly focused on non-fiction, and finds the Going Solo toolkit’s work record spreadsheet works well for her way of thinking, with the addition of ‘manuscript assessment’ as a category of work. Each round of editing the same book is logged as a separate job, which gives her enough data to analyse when it comes to pricing another job of the same stage.

2. Combining two off-the-shelf systems

IM Katherine Kirk uses both the work record from the Going Solo toolkit and Maya Berger’s TEA system (CIEP member discount available). Katherine is working towards PM status and finds the analysis and tracking offered in the jobs spreadsheet helps her to maintain a good record to support her application in due course. But she finds that TEA works better for her for financial records, and so she maintains both, having simply hidden the columns that are irrelevant to her business (columns N–S from the Going Solo spreadsheet).

Katherine uses the average words per hour for that particular kind of work to inform her estimates, but, depending on the client, may also do a sample edit to check. She records these sample edits in TEA in order to be prepared if that client comes back. If the client doesn’t return, Katherine has data ready to hand on the price she quoted, and can see what impact changing the price has on landing the client.

3. Tailored record-keeping

Nicky Taylor, an APM, has developed her own record-keeping system over the years. Like Jill, she records each type of work for the same book as separate jobs, so a development edit and a copyedit get their own rows in her spreadsheet.

Nicky said to me, ‘Looking at all my data made me realise that manuscript critiques on their own were simply not financially viable, so I stopped offering that service; if I hadn’t recorded everything, I doubt I would have known.’ Music to my ears about the real-world value of keeping business data.

For a development edit, Nicky records the onboarding time, reading time, report-writing time; for a copy- or line edit, she will record the time spent on each pass – she always does a full read-through and two passes, and has a column in her spreadsheet for each of these.

Included in her records are columns for pre-returning the job, which covers time for checking comments, checking over the style sheet and completing the handover tasks. Another column captures the time spent on post-edit revisions, post-edit discussions with the author, and emails. If a PDF conversion or layout work is required, this time also goes into that post-edit column.

Most of the time, the production of the style sheet is absorbed into the two passes, but may be recorded separately if the occasion demands. Production of a bible, perhaps for a planned series, will be logged separately.

Nicky includes an ‘Other’ column in her spreadsheet for different kinds of jobs, such as consultancy and other requests, recording the exact nature in the job description column. Like Katherine, Nicky also uses TEA for her financials.

The Going Solo toolkit: Work record spreadsheet

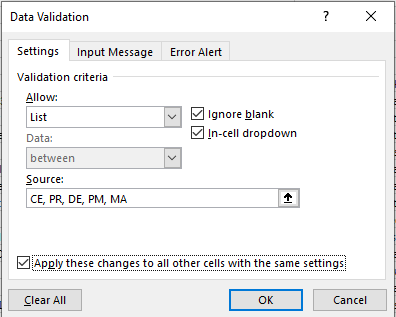

The CIEP has decided to follow Jill’s recommendation, and has added manuscript assessment to the dropdown list of types of work, which would include the kinds of tasks covered by Nicky’s ‘Other’ column. If you’re already using the spreadsheet and would like to add this to your own records, you can either download the new version (be sure to be logged in to the CIEP website first) and copy your records across, or extend that dropdown list yourself. It’s easy!

NB: All screenshots show Excel 365 on a PC. The instructions apply to PCs but Microsoft tells me they also work for Macs.

1. Select column ‘Type of work’ by clicking on the column header (D), which turns the column grey. A black down-arrow shows when your cursor is in the right position to select.

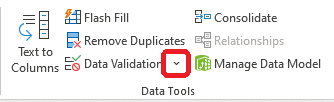

2. On the Data tab …

… open Data Validation in the Data Tools group by clicking the little down-arrow:

3. Select Data Validation from the dropdown menu:

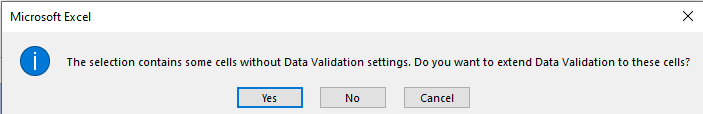

4. You’ll see this:

Click Yes.

5. You’ll see this:

Now you can type a comma, a space and MA into the end of the Source box.

Check the ‘Apply these changes to all other cells with the same settings’ box if you’ve added other tabs that have this same list, otherwise you can leave it blank.

It will look like this:

Click on OK.

You’re done! You can now use the new code, and you can, if you like, add others that suit the work you do. You might want to add consultancy as a category, for instance, if that makes sense for the work you do. You don’t have to use codes – you could spell out the entire word, or use a fuller abbreviation. Once you’ve got the hang of this, you can personalise your spreadsheet exactly as you like. That said …

Four reminders

Reminder #1

The Admissions Panel explained to me, when I was developing the Going Solo toolkit, that they want to see your copyediting and proofreading hours on your upgrade application, so remember to keep recording these clearly and separately, no matter what else you decide to record.

Reminder #2

If you’re not sure how to get the best use of the data you’ve gone to the trouble of collecting, see my earlier ‘Flying solo’ post on using the filter functions.

Reminder #3

The sooner you start keeping detailed records, the sooner you’ll have compiled a useful bank of data to help with price and time estimation for new jobs.

Reminder #4

If you’re inspired by Nicky’s level of detail, don’t forget that you can continue to personalise your own copy of the Going Solo toolkit work record. Inserting additional columns is easy!

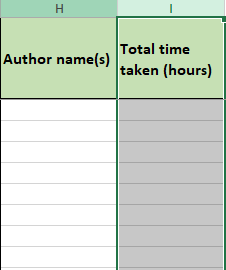

1. Click on the column letter immediately to the right of where you want to insert a new column.

Here, I’ve highlighted column I – see the colour change where the column’s label is, and the column itself has turned grey.

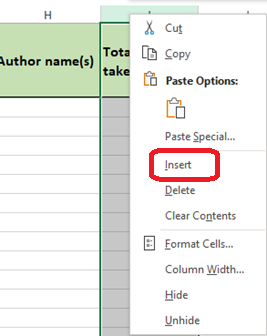

2. Right-click, then select Insert and a column will arrive between, in this example, Author name(s) and Total time taken (hours).

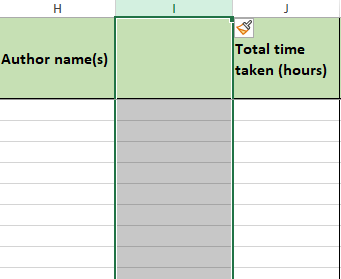

3. … and you will get this:

4. The Author name(s) column is still H, but Total time taken (hours) is now column J and we have a new, blank column I. Type in the name you want for the heading. Repeat as often as you need to add new columns, always clicking at the head of the column to the right of where you want to add a new one.

5. Columns in the wrong order? Move them with cut and paste. The column will always paste in to the left of where you click, as creating the new column did.

6. Unneeded columns? Instead of clicking on Insert, click on Delete if you’re sure you don’t want that column, or Hide, if you think you may need it at some point. (To unhide, select the columns on either side of the hidden column(s) and right-click; click on Unhide.)

Buy a print copy or download the second edition of Going Solo: Creating your freelance editorial business from here.

About Sue Littleford

Sue Littleford is the author of the CIEP guide Going Solo, now in its second edition. She went solo with her own freelance copyediting business, Apt Words, in March 2007 and specialises in scholarly humanities and social sciences.

Sue Littleford is the author of the CIEP guide Going Solo, now in its second edition. She went solo with her own freelance copyediting business, Apt Words, in March 2007 and specialises in scholarly humanities and social sciences.

About the CIEP

About the CIEP

The Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) is a non-profit body promoting excellence in English language editing. We set and demonstrate editorial standards, and we are a community, training hub and support network for editorial professionals – the people who work to make text accurate, clear and fit for purpose.

Find out more about:

Photo credits: office desk by Jessica Lewis Creative, laptop by Karolina Grabowska, both on Pexels.

Posted by Harriet Power, CIEP information commissioning editor.

The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the CIEP.